Review of Walter Salles Brazilian Film Behind The Sun

|

|

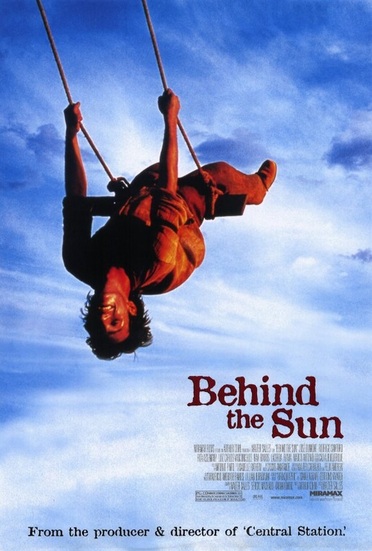

BEHIND THE SUN (2001)

SHINING BRIGHT

|

By Tom Clare

Behind The Sun (2001) Directed by Walter Salles. Brazil: 12. The success of Walter Salles’s 1998 classic Central Station symbolically marked the end of two decades of trauma for the Brazilian film industry. It was the harbinger of a new era of quality filmmaking not crippled by either insufficient funding or censorship at the hands of military dictatorships. For Salles, critical and commercial recognition at home and abroad (including two Oscar nominations) meant he had quickly become Latin-America’s most high-profile director. Three years down the road, he would direct his next feature, Behind the Sun (2001). This film is not the “Brazil in 2 hours” cultural rollercoaster that Central Station proved to be. Yet in many respects it feels just as personal a reflection of the director’s core values and highlights the diversity of his craft. A recurrent motif in almost all of his films is a journey of discovery to what Salles perceives to be the real heart of Brazil, its rural landscapes. Behind the Sun is set in 1910, setting its story against a backdrop of the gruelling, but beautiful, Sertao, the North-Eastern rural back lands of the country. It’s still Brazil, just in a different place, at a different time. |

The film’s simple, uncluttered narrative serves the audience another tale of tentative optimism, commenting on the importance of family and once again casting youthful characters as the lifeblood of the picture. It then contrasts them with an older generation who lose sight of basic values over intangible issues such as honour and tradition. It also shows Salles’s burgeoning ability to find a medium between the social-realist sensibilities of his Brazilian directing forbearers and the slick cinematography of modern Hollywood film.

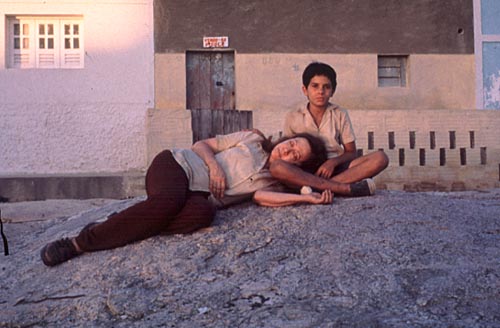

The story centres on two young sons of the Breves family, 20 year-old Tonio (Rodrigo Santoro) and his kid brother Pacu (Ravi Ramos Lacerda), who eke out a meagre living with their parents by harvesting sugar cane. We learn that they are caught up in a long-standing blood-feud with the Ferreira family, which dictates that one son must kill a son from the other family in order to retain their clan honour. An eye-for-an-eye process that continues unceasingly. After Tonio fulfils his duty, he must next face death. Granted a short-term truce that buys him a few weeks, he is told by the head of the Ferreira family ‘Your life is now split in two. The twenty years you’ve already lived, and the short time you have left.’ And thus much of the story charts what happens in that ‘short time’.

Early stages of the film expertly convey the desperate hardship of Tonio and Pacu’s lives toiling alongside their aggressive father and haggard mother. Repeated shots of oxen turning a giant a cog-wheel masterfully evokes a sense not only of the mindlessness of their lives, but also the cyclical nature of the violence Tonio and Pacu have been born into, particularly as the audience is given little insight as to how the feuding began or when it may end. The oxen, so used to being shepherded around the wheel, end up ambling about it out of habit – a shrewd nod to the son’s unquestioning nature as to their part in the ritual of dying. There’s a restless quality to the farm, with lots of fades and the use of vague inter-titles, used to imply that the passage of time has no bearing on their lives, one day much like the last. As Pacu puts it ‘we’re like the oxen here. We go round and round and never go anywhere.’

SOUNDS GOOD

Tonio becomes torn between family duty and his emotions when he meets the likable and eye-catching Clara (Flavia Marco Antonio), who is part of a travelling circus act. Inadvertently, she also has a profound influence on Pacu after giving him a picture book. Her stepfather names him (he was previously referred to simply as ‘Kid’), something his increasingly distant parents couldn’t bring themselves to do, perhaps anticipating he wouldn’t live to adulthood. Whilst Tonio becomes enamoured with the girl and longs for escape, it is Pacu’s efforts to concoct his own story that resonate most.

The story centres on two young sons of the Breves family, 20 year-old Tonio (Rodrigo Santoro) and his kid brother Pacu (Ravi Ramos Lacerda), who eke out a meagre living with their parents by harvesting sugar cane. We learn that they are caught up in a long-standing blood-feud with the Ferreira family, which dictates that one son must kill a son from the other family in order to retain their clan honour. An eye-for-an-eye process that continues unceasingly. After Tonio fulfils his duty, he must next face death. Granted a short-term truce that buys him a few weeks, he is told by the head of the Ferreira family ‘Your life is now split in two. The twenty years you’ve already lived, and the short time you have left.’ And thus much of the story charts what happens in that ‘short time’.

Early stages of the film expertly convey the desperate hardship of Tonio and Pacu’s lives toiling alongside their aggressive father and haggard mother. Repeated shots of oxen turning a giant a cog-wheel masterfully evokes a sense not only of the mindlessness of their lives, but also the cyclical nature of the violence Tonio and Pacu have been born into, particularly as the audience is given little insight as to how the feuding began or when it may end. The oxen, so used to being shepherded around the wheel, end up ambling about it out of habit – a shrewd nod to the son’s unquestioning nature as to their part in the ritual of dying. There’s a restless quality to the farm, with lots of fades and the use of vague inter-titles, used to imply that the passage of time has no bearing on their lives, one day much like the last. As Pacu puts it ‘we’re like the oxen here. We go round and round and never go anywhere.’

SOUNDS GOOD

Tonio becomes torn between family duty and his emotions when he meets the likable and eye-catching Clara (Flavia Marco Antonio), who is part of a travelling circus act. Inadvertently, she also has a profound influence on Pacu after giving him a picture book. Her stepfather names him (he was previously referred to simply as ‘Kid’), something his increasingly distant parents couldn’t bring themselves to do, perhaps anticipating he wouldn’t live to adulthood. Whilst Tonio becomes enamoured with the girl and longs for escape, it is Pacu’s efforts to concoct his own story that resonate most.

|

|

|

|

The book unlocks his imagination, bringing to life the best character in the film. He is the only figure who gives thought to how the feud might end, and his story about a mermaid (in this instance, Clara) makes for a beautiful and effective metaphor that comes full circle in the closing stages of the film. Once again Salles has managed to take a child actor from obscurity and manufacture an excellent performance. Lacerda’s exuberance serves to lighten the mood of an otherwise sombre film, putting in the shade Santoro’s competent, but forgettable, role as his elder brother, in a script that rarely gives him anything meaningful to say.

Mostly, the rest of the cast are decent, with the pick being Rita Assemany’s performance as the Breves mother. Grief stricken from the loss of so many children, her presence is hollow in the beginning, though her husband’s inability to break with brutal tradition triggers a subtle yet defined development in her character, as she becomes a fragile yet defiant figure. The soundtrack is eloquent and neatly employed, not instantly memorable, but makes for an ideal accompaniment to the action.

An inhospitable dust-bowl of a location is no barrier to Salles’s long-term collaborator and director of photography, Walter Carvalho, who has the uncanny knack of making the mundane appear glorious. The colour and lighting is of the Sertao is impossibly rich, meaning almost every shot of the landscape is a frame of art. Similarly, there’s a brightness and vitality to the carnival scenes, heightened by Clara’s fire dancing and rope swinging routines, though some might argue that it’s a less-expansive parallel to a similar night-time carnival in Central Station.

The setting could hardly have been more different from Central Station but this has all the hallmarks of a top-class Walter Salles movie. A number of first-time actors put in sterling displays, whilst the supreme cinematography and composition makes for a film that is gorgeous to look at. It isn’t quite as stimulating or emotively acted as the director’s finer works, but still comes highly recommended.

Mostly, the rest of the cast are decent, with the pick being Rita Assemany’s performance as the Breves mother. Grief stricken from the loss of so many children, her presence is hollow in the beginning, though her husband’s inability to break with brutal tradition triggers a subtle yet defined development in her character, as she becomes a fragile yet defiant figure. The soundtrack is eloquent and neatly employed, not instantly memorable, but makes for an ideal accompaniment to the action.

An inhospitable dust-bowl of a location is no barrier to Salles’s long-term collaborator and director of photography, Walter Carvalho, who has the uncanny knack of making the mundane appear glorious. The colour and lighting is of the Sertao is impossibly rich, meaning almost every shot of the landscape is a frame of art. Similarly, there’s a brightness and vitality to the carnival scenes, heightened by Clara’s fire dancing and rope swinging routines, though some might argue that it’s a less-expansive parallel to a similar night-time carnival in Central Station.

The setting could hardly have been more different from Central Station but this has all the hallmarks of a top-class Walter Salles movie. A number of first-time actors put in sterling displays, whilst the supreme cinematography and composition makes for a film that is gorgeous to look at. It isn’t quite as stimulating or emotively acted as the director’s finer works, but still comes highly recommended.

|

|

|

|

|

|