Review of Alfred Hitchcock Film Lifeboat

|

|

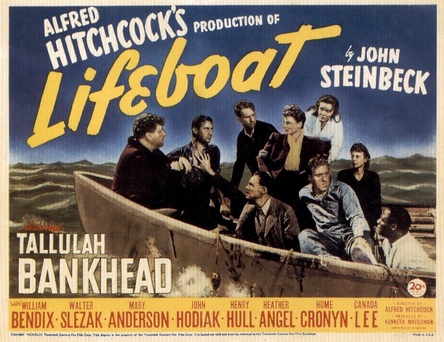

LIFEBOAT (1944)

CHARACTERS ADRIFT

'Who had the idea of booking a Thompson package holiday again?'

By Tom Clare

Lifeboat (1944)

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. USA: PG.

Lifeboat’s yarn is a devilishly simple one. The setting is World War II, take a bunch of American survivors adrift in the middle of the ocean after being torpedoed, then add to their number the Nazi responsible, and you’ve got the basic ingredients for a tense and absorbing thriller. Theory and practice don’t quite come together as one here though, and the last of Hitchcock’s trio of media-at-war features filmed and set during the period (following Foreign Correspondent (1940) and 1942’s Saboteur) is something of a noble failure.

The film, set entirely on a lifeboat, was beset with problems during filming. Most of the cast fell ill at one point or another, likely as a result of scenes that repeatedly see them drenched with water, and one even suffering cracked ribs. Troubles continued post-release, with the film experiencing only a short-lived cinema run in the United States, following criticism over the humanising of a Nazi character.

Viewing Lifeboat after the event though, the reaction seems puzzling, as such a brave portrayal of ‘the old enemy’ never really comes to fruition; it’s a theme that’s tentatively ventured, but never pursued with any great conviction. Hitchcock retraces a trope he used successfully in Saboteur of using a small cross-section of civilised society (the Americans) to judge an accused outsider (in this case, the Nazi). In Saboteur, the balance and counter-balance of viewpoints within a micro-democracy that weighs up a character’s fate made for riveting viewing, but in Lifeboat the message seems confused, the sentiment empty. The German in question, Willie (Walter Slezak), bounces back and forth between the ‘human’ Hitchcock seems to want to emphasise, and an entirely stereotypical Nazi villain that the censors would likely have appreciated in an era of Casablanca-inspired movies that were as much a call-to-arms as an hour and a half’s entertainment.

That’s not to be too critical of such movies, as many were fantastic in their own right; it’s just that Willie’s intermittent good deeds are punctuated by a litany of underhand, treacherous acts and overt, sly looks, unintentionally giving him the air of a silent-era comic goon. What begins as a brave venture in characterising the effects war has on the individuals caught up in it soon descends into a piece of propaganda so heavy-handed that it borders on scaremongering, and is quite at odds with Hitchcock’s subtler wartime efforts.

With the whole of the story unfolding within the confines of the boat, a lot rests on the characters and unfortunately, the archetypes on show are mostly too dull to follow with any great conviction. Lifeboat’s main source of vitality centres around cold, high-maintenance journalist Constance “Connie” Porter (Tallulah Bankhead), and her occasionally sparky tête-à-têtes with walking teeth-whitener advertisement John Kovac (John Hodiak). Whilst both are too abrasive to be truly likeable, they do nevertheless have their moments, particularly in early exchanges when Kovac likens her obsession with reporting the war to a Broadway play; ‘and if enough people die before the last act, maybe you might give it four stars’. It remains one of the most enduringly acerbic lines to feature in the director’s work.

THAT SINKING FEELING

Despite a neat motif of shedding social-status through the loss of material possessions, Porter remains too aloof a figure to ever seem like a fit for her opposite number, and the pairing never quite convinces. Bankhead’s excessive make-up doesn’t help here; she looks every inch the Hollywood glamour queen to begin with which, in lieu of her appearance being alluded to by other characters and Porter’s generally self-absorbed nature, can be forgiven in the early stages, but as the film progresses her radioactive glow looks more and more out of place, whilst tidal waves and days without food barely leave her with a hair out of place. As with such uneasy unions, the pair’s most watchable scenes are their coming to blows, whilst the quieter moments, such as Porter querying the meaning of Kovac’s tattoos, are listless and uninteresting.

Elsewhere, Hitchcock appears to have gone box-ticking crazy. You’ve got the hysterical mother; two insipid souls who seemingly serve no purpose other than to form a bland relationship; a rich oil tycoon; a black subservient type who is treated as condescendingly as possible (referred to by the non-PC nickname of ‘Charcoal’ – something the story’s writer, John Steinbeck, was not at all pleased about) and last but not least the easy-going, jovial injured soldier who regales us with some generic tales about how great home life is and how much he wants to get back to his (frankly quite dodgy-sounding) girlfriend Rosie. All fulfil their given roles, though none with any great panache.

Lifeboat (1944)

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. USA: PG.

Lifeboat’s yarn is a devilishly simple one. The setting is World War II, take a bunch of American survivors adrift in the middle of the ocean after being torpedoed, then add to their number the Nazi responsible, and you’ve got the basic ingredients for a tense and absorbing thriller. Theory and practice don’t quite come together as one here though, and the last of Hitchcock’s trio of media-at-war features filmed and set during the period (following Foreign Correspondent (1940) and 1942’s Saboteur) is something of a noble failure.

The film, set entirely on a lifeboat, was beset with problems during filming. Most of the cast fell ill at one point or another, likely as a result of scenes that repeatedly see them drenched with water, and one even suffering cracked ribs. Troubles continued post-release, with the film experiencing only a short-lived cinema run in the United States, following criticism over the humanising of a Nazi character.

Viewing Lifeboat after the event though, the reaction seems puzzling, as such a brave portrayal of ‘the old enemy’ never really comes to fruition; it’s a theme that’s tentatively ventured, but never pursued with any great conviction. Hitchcock retraces a trope he used successfully in Saboteur of using a small cross-section of civilised society (the Americans) to judge an accused outsider (in this case, the Nazi). In Saboteur, the balance and counter-balance of viewpoints within a micro-democracy that weighs up a character’s fate made for riveting viewing, but in Lifeboat the message seems confused, the sentiment empty. The German in question, Willie (Walter Slezak), bounces back and forth between the ‘human’ Hitchcock seems to want to emphasise, and an entirely stereotypical Nazi villain that the censors would likely have appreciated in an era of Casablanca-inspired movies that were as much a call-to-arms as an hour and a half’s entertainment.

That’s not to be too critical of such movies, as many were fantastic in their own right; it’s just that Willie’s intermittent good deeds are punctuated by a litany of underhand, treacherous acts and overt, sly looks, unintentionally giving him the air of a silent-era comic goon. What begins as a brave venture in characterising the effects war has on the individuals caught up in it soon descends into a piece of propaganda so heavy-handed that it borders on scaremongering, and is quite at odds with Hitchcock’s subtler wartime efforts.

With the whole of the story unfolding within the confines of the boat, a lot rests on the characters and unfortunately, the archetypes on show are mostly too dull to follow with any great conviction. Lifeboat’s main source of vitality centres around cold, high-maintenance journalist Constance “Connie” Porter (Tallulah Bankhead), and her occasionally sparky tête-à-têtes with walking teeth-whitener advertisement John Kovac (John Hodiak). Whilst both are too abrasive to be truly likeable, they do nevertheless have their moments, particularly in early exchanges when Kovac likens her obsession with reporting the war to a Broadway play; ‘and if enough people die before the last act, maybe you might give it four stars’. It remains one of the most enduringly acerbic lines to feature in the director’s work.

THAT SINKING FEELING

Despite a neat motif of shedding social-status through the loss of material possessions, Porter remains too aloof a figure to ever seem like a fit for her opposite number, and the pairing never quite convinces. Bankhead’s excessive make-up doesn’t help here; she looks every inch the Hollywood glamour queen to begin with which, in lieu of her appearance being alluded to by other characters and Porter’s generally self-absorbed nature, can be forgiven in the early stages, but as the film progresses her radioactive glow looks more and more out of place, whilst tidal waves and days without food barely leave her with a hair out of place. As with such uneasy unions, the pair’s most watchable scenes are their coming to blows, whilst the quieter moments, such as Porter querying the meaning of Kovac’s tattoos, are listless and uninteresting.

Elsewhere, Hitchcock appears to have gone box-ticking crazy. You’ve got the hysterical mother; two insipid souls who seemingly serve no purpose other than to form a bland relationship; a rich oil tycoon; a black subservient type who is treated as condescendingly as possible (referred to by the non-PC nickname of ‘Charcoal’ – something the story’s writer, John Steinbeck, was not at all pleased about) and last but not least the easy-going, jovial injured soldier who regales us with some generic tales about how great home life is and how much he wants to get back to his (frankly quite dodgy-sounding) girlfriend Rosie. All fulfil their given roles, though none with any great panache.

|

|

|

|

Dialogues do a decent job of conveying the psychological impact the passage of time has on the crew of the lifeboat, as hunger and thirst lead to frayed emotions and a creeping paranoia amongst the survivors, which is smartly expressed. Unfortunately, much like the lifeboat itself, the film drifts along without any major surprises; with the characters not amounting to enough in themselves to solely propel the story. Seemingly happy to paper over characters’ behavioural inconsistencies, the ending is convenient and unimaginative, attempting more of a tidy-up than a punchy finale.

Pluses include the impressive sets, whereby a model boat was utilised and kept in motion at all times during filming for the sake of realism, whilst mist effects helped it garner a certain atmosphere. The night-time scenes and general attention to detail impresses, making for fuller, more convincing compositions than many of its contemporaries; not necessarily enough to fool you that they’re really out at sea, but near enough. Hitchcock’s imaginative ‘cameo’ raises a smile, in this instance popping up in a newspaper advertisement for the fictional Reduco Obesity Slayer. The cinematography, even in such a restrictive, limiting environment, creates some of the director’s trademark unease, particularly when Kovac is deciding the fate of their Nazi captive, the camera crashes around the boat as we see his rain-soaked, indistinct features, as the shot cleverly reflects both the stormy conditions and the mind-set of a character on the verge of losing control.

Lifeboat is ultimately unsuccessful for a few core reasons; the story relies too heavily on a largely stationary cast, who in turn mostly comprise of forgettable personalities, and without any major plot twists or events, it drifts along in neutral for much of its running time. As the film seems unsure as to whether to portray Willie as an outright villain or a war victim, he becomes a muddle, and as if to emphasise this, he paradoxically saves and kills the same individual within the film.

You can’t help but feel it would have been better if there was a blurring of the moral margins, rather than every deed being judged in black or white terms. As it is, you end up caring little for the ‘goodies’ or the ‘baddies’, and the portrayal of the strong-as-iron Nazi Übermensch is so flagrant it appears almost a caricature. The notion of the Nazis being something more than human is a disquietingly feasible one amidst the worries of war in 1944, even if Willie’s extraordinary feats of endurance in Lifeboat can be taken with a pinch of salt. Watchable, but by no means essential.

Pluses include the impressive sets, whereby a model boat was utilised and kept in motion at all times during filming for the sake of realism, whilst mist effects helped it garner a certain atmosphere. The night-time scenes and general attention to detail impresses, making for fuller, more convincing compositions than many of its contemporaries; not necessarily enough to fool you that they’re really out at sea, but near enough. Hitchcock’s imaginative ‘cameo’ raises a smile, in this instance popping up in a newspaper advertisement for the fictional Reduco Obesity Slayer. The cinematography, even in such a restrictive, limiting environment, creates some of the director’s trademark unease, particularly when Kovac is deciding the fate of their Nazi captive, the camera crashes around the boat as we see his rain-soaked, indistinct features, as the shot cleverly reflects both the stormy conditions and the mind-set of a character on the verge of losing control.

Lifeboat is ultimately unsuccessful for a few core reasons; the story relies too heavily on a largely stationary cast, who in turn mostly comprise of forgettable personalities, and without any major plot twists or events, it drifts along in neutral for much of its running time. As the film seems unsure as to whether to portray Willie as an outright villain or a war victim, he becomes a muddle, and as if to emphasise this, he paradoxically saves and kills the same individual within the film.

You can’t help but feel it would have been better if there was a blurring of the moral margins, rather than every deed being judged in black or white terms. As it is, you end up caring little for the ‘goodies’ or the ‘baddies’, and the portrayal of the strong-as-iron Nazi Übermensch is so flagrant it appears almost a caricature. The notion of the Nazis being something more than human is a disquietingly feasible one amidst the worries of war in 1944, even if Willie’s extraordinary feats of endurance in Lifeboat can be taken with a pinch of salt. Watchable, but by no means essential.

|

|

|

|

|

|