The Atomic Age on Film: Nuclear Arms Development and War History in 20th Century Film

|

|

THE ATOMIC AGE ON FILM

NUCLEAR ARMS DEVELOPMENT AND WAR HISTORY IN FILM

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts

Focusing primarily on American Nuclear Arms Development and war history, we explore how technology has been reflected in the movies of the last half-century as a product of the era they were made in.

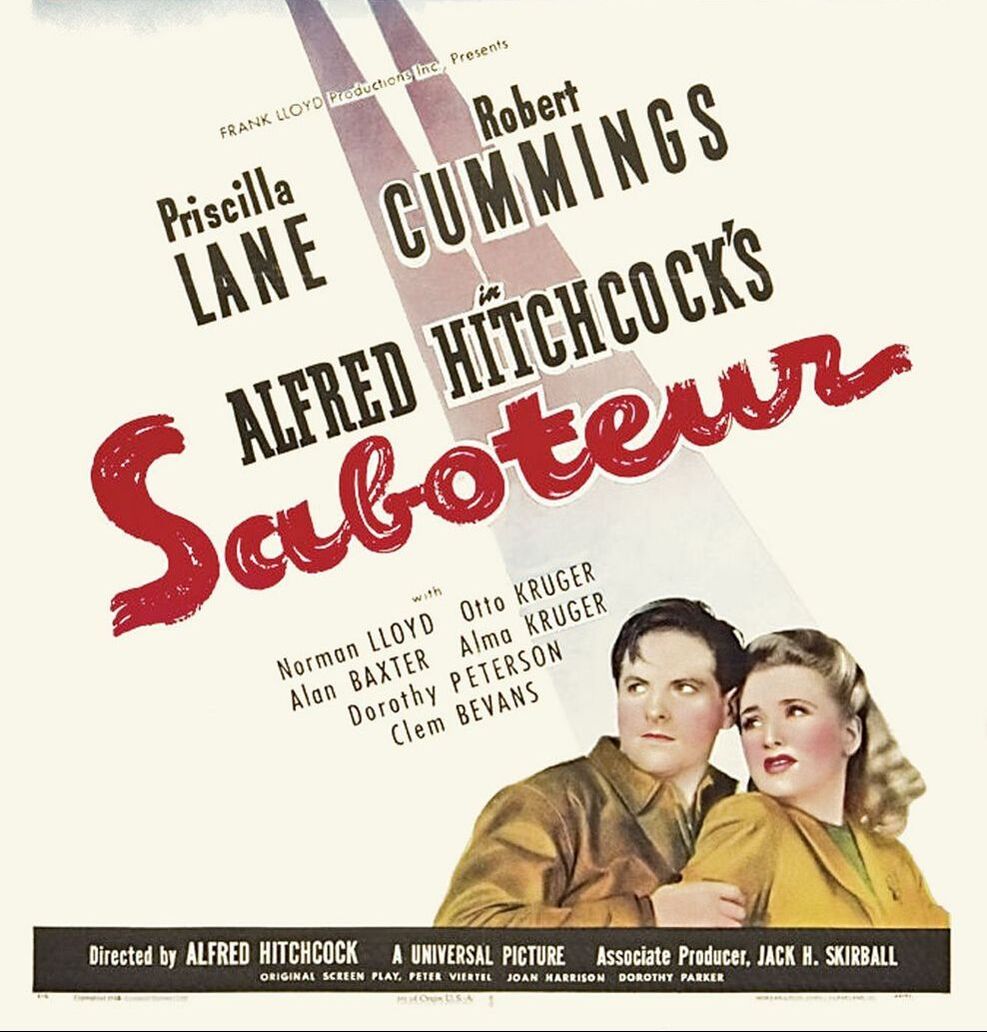

Atomic weapons were a part of big screen entertainment and literature long before they were made in the real world. In fact, the author of a novel credited as the basis of Starship Troopers (1997) may even have been partially responsible for influencing President Truman to authorise the first ever use of an atomic weapon on living targets. Robert Heinlein (Starship Troopers, 1959 – the book) was famous for his pro super-weapons stance in the early 1940s, writing stories that suggested that the use of atomic weapons would secure America from future international conflict.

After Hiroshima was annihilated in 1945 and other nations developed atomic capabilities, there was a radical change in films regarding super-weapons, as science fiction became science fact. Weapons of mass destruction were no longer viewed as a saviour of nations, as in Murder in the Air (1940), but viewed as a threat to the survival of the human species by an unnatural force that was taking on a life of it’s own, epitomized by Godzilla (Godzilla, 1955), a Japanese film that did well at the American box office. The negative effects of atomic technology became a regular depiction in films.

By the time of the Vietnam War in the 1960s Heinlein’s philosophy was rapidly becoming less credible, and tolerance for nuclear weapons by the American public diminished. Although the Cold War discouraged direct conflict against America, it simply meant that the superpowers ‘now fought one another through intermediaries in what they regarded as peripheral theatres.’[1] As American troops were forced to become involved in one of these ‘peripheral theatres’ in Vietnam, Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara’s announcement in 1965 that the United States was relying upon the threat of ‘mutually assured destruction’ to deter a Soviet attack became less reliable in the opinion of liberals (and McNamara among them).

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts

Focusing primarily on American Nuclear Arms Development and war history, we explore how technology has been reflected in the movies of the last half-century as a product of the era they were made in.

Atomic weapons were a part of big screen entertainment and literature long before they were made in the real world. In fact, the author of a novel credited as the basis of Starship Troopers (1997) may even have been partially responsible for influencing President Truman to authorise the first ever use of an atomic weapon on living targets. Robert Heinlein (Starship Troopers, 1959 – the book) was famous for his pro super-weapons stance in the early 1940s, writing stories that suggested that the use of atomic weapons would secure America from future international conflict.

After Hiroshima was annihilated in 1945 and other nations developed atomic capabilities, there was a radical change in films regarding super-weapons, as science fiction became science fact. Weapons of mass destruction were no longer viewed as a saviour of nations, as in Murder in the Air (1940), but viewed as a threat to the survival of the human species by an unnatural force that was taking on a life of it’s own, epitomized by Godzilla (Godzilla, 1955), a Japanese film that did well at the American box office. The negative effects of atomic technology became a regular depiction in films.

By the time of the Vietnam War in the 1960s Heinlein’s philosophy was rapidly becoming less credible, and tolerance for nuclear weapons by the American public diminished. Although the Cold War discouraged direct conflict against America, it simply meant that the superpowers ‘now fought one another through intermediaries in what they regarded as peripheral theatres.’[1] As American troops were forced to become involved in one of these ‘peripheral theatres’ in Vietnam, Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara’s announcement in 1965 that the United States was relying upon the threat of ‘mutually assured destruction’ to deter a Soviet attack became less reliable in the opinion of liberals (and McNamara among them).

|

‘MANIACS! YOU BLEW IT UP!’[2]

The 1960s film Planet of the Apes (1968) reflects this attitude in its final frames, as a misanthropic Taylor (Charlton Heston) discovers a washed up Statue of Liberty and falls to his knees shouting ‘Maniacs! You blew it up!’, revealing the madhouse theme of the film to be an allegory for contemporary society. But unlike our society, Dr Zaius (Maurice Evans) has prevented nuclear holocaust for the Simians by denying technological and scientific progress. All that remains of human civilisation in 2000 years’ time is technological evidence of our weak and fragile state (false teeth, a heart valve, eye glasses) and our lost innocence (a child’s doll), supporting liberal hippy ideals of a simple and less technological lifestyle by pointing out the futility of technological progression. |

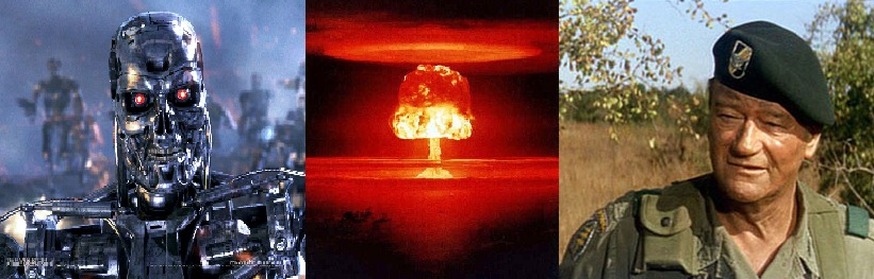

And when the world is eventually destroyed in the sequel, Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1969), it is because a human (Taylor) has used advanced technology to travel forward in time and ignite a nuclear warhead, the legacy of mankind (Interestingly, this time-travel plot would be reversed for the eighties film The Terminator (1984), emphasising that our ‘legacy’ is also a contemporary problem). It could even be argued that Taylor’s misanthropic character is a product of the atomic age, highlighting fears of an America journeying into the future while trapped in a nuclear stalemate. This type of character existed before Hiroshima, but they are treated more seriously in films during the Cold War. In fact it is not until the fall of the Soviet Union that they become comedic figures, with Mr Pink in Reservoir Dogs (1991) and much of Steve Buscemi’s career thereafter.

|

The presence of the Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes may even be an indicator of a new age of atomic guilt. In 1963 the District Court of Tokyo declared that the ‘aerial bombardment with atomic bombs of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was an illegal act of hostilities according to the rules of international law. It must be regarded as indiscriminate aerial bombardment of undefended cities’.[3]

This realisation of loss of innocence on the part of America was accepted by the new counter-culture, wanting to make amendments. That same year the Vatican issued a letter by Pope John XXIII entitled Pacem in Terris calling for an end to the nuclear arms race. The film reflects this in the character of Dr Ziaus, who as Minister of Science and Chief Defender of the Faith is able to put into practice what the Pope had suggested.[4] Scenes set in space in the film seem to echo nuclear concerns of the time, rather than space exploration, with the moon landing still a year away. The previous year (1967) had witnessed the implementation of The Outer Space Treaty[5] between Washington, Moscow and London, declaring that neither of them would ‘place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction’. |

[1] Niall Ferguson, The War of the World, page 613.

[2] Taylor, Planet of the Apes (1968) [3] NuclearFiles.org [4] According to Richard Von Busack’s theory of the science fiction film’s hero, Dr Zaius manages to be the mediator between the opposing forces of the military man (the gorillas) and the scientist (the chimps), which explains that while he is a villain in the film, he is also , debatably, correct most of the time and not entirely loathsome. Richard Von Busack, Signifying monkeys: politics and story-telling in the planet of the apes series, The science fiction film reader, Limelight, 2004, p169. |

So when Taylor asks ‘Does man still make war with his brother?’ aboard his spaceship, it also reflects his position of neutrality in space. Perhaps acting symbolically, it is only when Taylor’s craft re-enters Earth’s atmosphere that it comes to destruction, having been tossed and turned from the tranquillity and serenity of space back into a world that accommodates conflict.

|

|

Green Berets: Now you see, Timmy...

BUT THERE ARE NO CUBANS IN VIETNAM!

Planet of the Apes does not specify who launched the first nuclear missile, taking the wider view of the issue as a global problem for all of humanity, rather than any one nation, (although with the destruction of the Statue of Liberty it does seem to suggest that America needs to lead by example). However The Green Berets (1968), although made in the same year, has no reservations about identifying an enemy and suggesting extreme foreign policy to combat them. A scene at the beginning of the film suggests that Soviet Russia and Communist China (who began thermonuclear weapons testing in 1967) are providing weapons to the Vietcong, (which is historically true), but it negates the fact that the American military was better equipped and had greater resources. The film takes the view that advanced military technology is a positive thing, demonstrating the brutality of the North Vietnamese primitive punji sticks booby traps, with the murder of an American soldier. In reality these booby traps ‘did not kill en masse’, but were used to ‘traumatize enemy troops psychologically’[6].

|

[5] The treaty was signed on January 27th 1967 and entered into force on October 10th. The full title is: The Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.

[6] American Experience http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/vietnam/

timeline/tl3.html#a (Link now expired) [7] Niall Ferguson, The War of the World, page 618. [8] NuclearFiles.org |

But the real aim of the scene at the beginning of the film seems to be the feeding on American xenophobia associated with the weapons of ‘others’. By setting up the film with a showcase of Soviet weapons being used by other nations, the film makers are using the fear and paranoia of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis to sway the public into accepting their viewpoint, rather than that of the liberal media.

Later on, the film also demonstrates a worship of aerial bombardment, as the USAF repel an attack by swiftly killing hundreds of Vietcong, pleasing John Wayne’s character immensely. Although they are not dropping nuclear weapons, the effect is the same, as Vietnam witnessed ‘strategic bombing raids on a scale that ultimately matched the combined efforts of all the air forces in the Second World War.’[7] However this scope of aerial bombardment would not be conveyed in a Vietnam War movie until the 1970’s Apocalypse Now (1979), |

perhaps inspired by a renewed fear of Nuclear weapons due to America’s development of the neutron bomb in 1977.

During the later years of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal encouraged a lack of confidence in the public view of authorities that would later be reflected in characters in The Terminator, which even included scenes that mirrored the car park paranoia of All the President’s Men (1976). By the early 1980s Americans had become doubtful regarding the people in charge of ‘the button’, and this was reflected in politicians’ agendas of the time. In 1981 President Jimmy Carter painted a picture of nuclear holocaust in his farewell address stating:

‘In an all-out nuclear war, more destructive power than in all of World War II would be unleashed every second during the long afternoon it would take for all the missiles and bombs to fall. A World War II every second. More people would be killed in the first few hours than all the wars of history put together. The survivors, if any, would live in despair amid the poisoned ruins of a civilisation that had committed suicide.’[8]

Succeeded by President Ronald Reagan, nuclear fears grew evermore urgent. Reagan, sharing Heinlein’s pro-weapons of mass destruction beliefs, ended two decades of negotiation by removing the United States from the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 1982, and then called upon the scientific community to devise a space-based defence system in his Star Wars speech of 1983. An eventual nuclear holocaust seemed inevitable in the public consciousness. This culminated in the ABC television programme The Day After (1983), which depicted a fictional account of a post-apocalyptic America to over 100 million viewers.

During the later years of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal encouraged a lack of confidence in the public view of authorities that would later be reflected in characters in The Terminator, which even included scenes that mirrored the car park paranoia of All the President’s Men (1976). By the early 1980s Americans had become doubtful regarding the people in charge of ‘the button’, and this was reflected in politicians’ agendas of the time. In 1981 President Jimmy Carter painted a picture of nuclear holocaust in his farewell address stating:

‘In an all-out nuclear war, more destructive power than in all of World War II would be unleashed every second during the long afternoon it would take for all the missiles and bombs to fall. A World War II every second. More people would be killed in the first few hours than all the wars of history put together. The survivors, if any, would live in despair amid the poisoned ruins of a civilisation that had committed suicide.’[8]

Succeeded by President Ronald Reagan, nuclear fears grew evermore urgent. Reagan, sharing Heinlein’s pro-weapons of mass destruction beliefs, ended two decades of negotiation by removing the United States from the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty in 1982, and then called upon the scientific community to devise a space-based defence system in his Star Wars speech of 1983. An eventual nuclear holocaust seemed inevitable in the public consciousness. This culminated in the ABC television programme The Day After (1983), which depicted a fictional account of a post-apocalyptic America to over 100 million viewers.

|

|

|

[9] With homosexuality declassed as a psychiatric illness in America in 1973 the action films of the 70s saw an increase in the extremities of masculine heterosexual assertion (Lee Marvin, Clint Eastwood), and Arnold Schwarzenegger certainly falls into this category of movie protagonists. However his role in The Terminator could also be interpreted as being homosexual, as it involves wearing denim and leathers and acting as an object of scopophilia for a male gaze. Erotic overtones have been associated with robots ever since the Maria (Brigitte Helm) doppelganger in Metropolis (1926), however although she serves as a fantasy to men watching, the Terminator does not necessarily appeal to women in the same way. Perhaps the root of this is the same reason why more men purchase blow-up sex dolls than women.

|

The opening scene of The Terminator the following year reflects this nuclear holocaust-fearing culture, depicting a world destroyed by machines, with the surviving humans constantly battling for survival ‘amid the poisoned ruins’. By sending one of these machines back in time the film highlights the contemporary need to take preventative action. In this way the film reflects the cause of disarmament, which had become more popular than ever, with New York witnessing the largest anti-war demonstration of all history in 1982.

There was also a growing mistrust of technology in films of the 1980s as computers and games consoles became household items (particularly the Nintendo, launched in 1983). The use of these domestic computers was mostly the domain of the male and provided a world for boys to enter that was remote to most women. However at the same time, women were also becoming more independent. This second wave feminism resulted in films such as The Terminator, which depicted a woman under threat from machines (a walkman, a pager and other everyday items adding to her problems, as well as the uber-masculine robot[9]). In line with the beliefs of Reagan’s strategic defence administration and economic policies of the time, the film portrays an attacking technology as only being beatable by counteractive technology (and corporate industrialised technology at that, considering the setting of the robot’s demise). ‘WHAT? I SEE, JUST ASK FOR OMSK INFORMATION.’[10]

While the gung-ho attitude of Rambo in 1985’s Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) reflected the Reagan Administration’s stance on treaties and international bureaucracy (Reagan declared that the antiballistic defence system in space was not in violation of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, despite it

|

clearly being so), by the mid 1990s the political landscape had changed, and depictions of nuclear power along with it. The Chernobyl power plant disaster in 1986, although not a product of the nuclear arms program, became an example of the dangers inherent in such endeavours. A general mistrust of technology had also grown ever more, with the news broadcasting footage in 1988 of a fatal crash of an A320 Airbus due to a computer that would not allow pilots to make course corrections. It had become evident that technology was increasingly problematic, and not the utopian ideal of the 1950s.

|

However, with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, nuclear brinksmanship pressures eased and massive disarmament on both sides could finally be realised. This began with the Bush administration’s cancellation of the Midgetman Missile Program, a halt on production of W-88 warheads, MX2 test missiles, B-2 bomber planes and cruise missiles in 1992, and the signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty in 1993.

It was then followed in 1994 by President Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin’s announcement that from herein no countries would be targeted by nuclear weapons, a plan to end nuclear testing by September 1996, and a vote in the United Nations General Assembly to consider if ‘the threat or use of nuclear weapons in any circumstances is permitted under international law?’[11] And this has clearly had an effect on the films of the time. |

When America is under attack from weapons of mass destruction in Independence Day (1996), President Whitmore (Bill Pullman) struggles with the decision to retaliate using a nuclear missile. In fact he is only willing to use it after all attempts at communication with the aliens have failed, even after they have already destroyed every major American city. Even then, he is only convinced to employ it after an alien directly informs him that their intention is exclusively hostile and that they are not open to negotiation. After he does finally authorise its use, it proves to be an ineffective means of defence, the only thing able to save the world at the end of the film still proving to be communication (and the ones who were unwilling to use it being destroyed).

And so it is safe to assume, for the sake of this article at least, that we can interpret the aliens of Independence Day as a metaphor for nuclear weapons. They first arrive in 1947 at Roswell, a site synonymous with the birth of the atomic age. They strike fear into the hearts of entire populations, we can not communicate with them, their only intention is mass destruction, they attack from the sky, and there are no military weapons that can shoot them down (until all nations have co-operated). Produced fifty years after the end of the Second World War, and only a few years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the film seems to be acting as a Dear John letter to the Cold War. It suggests that in the end America survived the nuclear brinksmanship despite technological advances and military might, rather than as Reagan’s policies encouraged in the 1980s, because of it.

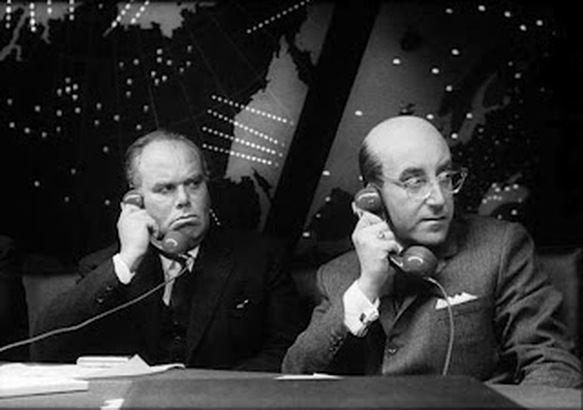

The repetitive use of telephones in several scenes to communicate with loved ones in Independence Day embodies the 1990s embrace of the Hot Line Agreement of 1963 to communicate with Russia on nuclear matters, which was excellently spoofed in Dr Strangelove (1964).

But there is no such mockery of it in this film. Instead, it shows how communication between America and the nuclear states of Russia and China, (and also the nuclear-hungry States of Israel, Pakistan and, dare we suggest it these days, Iraq!), saves the day from what was once feared as the most likely outcome of the Cold War (the destruction of cities from above). Of course this communication is more of a dictation by the Americans than a discourse with other nations, but the results are still positive and everyone is grateful for their help (sounds like a Foreign Secretary’s wet dream).

It is only fitting that the film concludes with shots of Egypt and Kilimanjaro triumphing over these destructive spacecraft, as the African nations declared the continent a Nuclear Weapons Free Zone only a few months before its release, pledging never to build, or test or stockpile nuclear weapons.

But there is no such mockery of it in this film. Instead, it shows how communication between America and the nuclear states of Russia and China, (and also the nuclear-hungry States of Israel, Pakistan and, dare we suggest it these days, Iraq!), saves the day from what was once feared as the most likely outcome of the Cold War (the destruction of cities from above). Of course this communication is more of a dictation by the Americans than a discourse with other nations, but the results are still positive and everyone is grateful for their help (sounds like a Foreign Secretary’s wet dream).

It is only fitting that the film concludes with shots of Egypt and Kilimanjaro triumphing over these destructive spacecraft, as the African nations declared the continent a Nuclear Weapons Free Zone only a few months before its release, pledging never to build, or test or stockpile nuclear weapons.

|

|

THE DISARMAMENT PIROUETTE

Unfortunately, only a year after the declaration of peaceful world unity in Independence Day, the world saw the Russians lose ‘a hundred suitcase-sized nuclear bombs capable of killing 100,000 people each’[12], NASA launching a probe carrying 72.3 pounds of plutonium despite international protests, the U.S. military testing satellite disabling lasers in space against Russian requests, and a new Presidential Decision Directive that allows nuclear retaliation in response to chemical or biological weapons attack. Films were now shifting their focus away from the prospect of global destruction by nuclear attack, but were still concerned about an America that had nuclear weapons, but no ideological enemy.

This return to Heinlein’s superpower attitude for America in a post-Cold War world culminated in the film Starship Troopers the following summer. By viewing the destruction of Hiroshima as a pro-nuclear argument, the ideology observed in the film states that ‘naked force has resolved more issues in history than any other factor’[13].

Unfortunately, only a year after the declaration of peaceful world unity in Independence Day, the world saw the Russians lose ‘a hundred suitcase-sized nuclear bombs capable of killing 100,000 people each’[12], NASA launching a probe carrying 72.3 pounds of plutonium despite international protests, the U.S. military testing satellite disabling lasers in space against Russian requests, and a new Presidential Decision Directive that allows nuclear retaliation in response to chemical or biological weapons attack. Films were now shifting their focus away from the prospect of global destruction by nuclear attack, but were still concerned about an America that had nuclear weapons, but no ideological enemy.

This return to Heinlein’s superpower attitude for America in a post-Cold War world culminated in the film Starship Troopers the following summer. By viewing the destruction of Hiroshima as a pro-nuclear argument, the ideology observed in the film states that ‘naked force has resolved more issues in history than any other factor’[13].

|

[12] NuclearFiles.org [13] As said by teacher Jean Rasczak (Michael Ironside) at the beginning of the film. |

However it shows us a world where nuclear weapons are used so casually that they have lost all value as a deterrent, the use of which can be authorised by soldiers in the field of combat. It is a technology like any other that surrounds and weaves into peoples’ lives in the film.

Fittingly the ‘nukes’ are administered by panzer Faust, a Nazi invention, that also highlights the loss of capacity for sympathy in this world of superpower, where the enemies are viewed as bugs. |

Interestingly, it is also a panzer Faust that Rambo ultimately turns to in order to defeat the Russians in Rambo: First Blood Part II, demonstrating the technological legacy of Operation Paperclip, when America employed former Nazi scientists in order to keep up with Russians’ technological developments. By using the weapon to finally defeat the Soviets at the end of the film, it seems to justify the American use of Nazis, who also shared an aggressive foreign policy like Reagan.

In Starship Troopers even medical technology is seen as warping human capacity for sympathy, as it allows drill instructors to break limbs and penetrate hands with knives in order to use cadets as examples. Because they can be so easily healed, the people of this world do not consider the body to be anything more than flesh, and momentary pain viewed as character building.

Essentially, the film is suggesting that the more we let technology into our lives, the less human or humane we become, characters with grotesque and exaggerated prosthetic limbs making it a visual point in the film. Meanwhile, in the world of 1990s America, children have their perceptions of war warped and distanced by computer games, echoing news footage of the Gulf War that sanitises it and eradicates the human factor. The treatment of cadets by the Federation reflects the American administration’s post-Cold War attitude that they can now probably get away with anything, as there are fewer powerful bodies to prevent them (the nadir of which would end up being Bush’s 21st century Gulf War that was in direct violation of the United Nations orders).

Of course that war itself was paralleled by Munich (2004) in which an Israeli counter terrorist group sought revenge for the 1972 Olympic murders, just as President Bush invaded Iraq and Afghanistan, supposedly in retaliation for atrocities against America. And on a related note Hostel (2005) shows that news media have made an effort to return the human factor to war, as it mirrors the treatment of prisoners in Abu Grabe and Guantanamo Bay during that second Gulf War, but does not bode well for American perceptions of the Bush administration. It will be interesting to see how nuclear arms disarmament unfolds during the Obama administration, and how it will be reflected on film.

In Starship Troopers even medical technology is seen as warping human capacity for sympathy, as it allows drill instructors to break limbs and penetrate hands with knives in order to use cadets as examples. Because they can be so easily healed, the people of this world do not consider the body to be anything more than flesh, and momentary pain viewed as character building.

Essentially, the film is suggesting that the more we let technology into our lives, the less human or humane we become, characters with grotesque and exaggerated prosthetic limbs making it a visual point in the film. Meanwhile, in the world of 1990s America, children have their perceptions of war warped and distanced by computer games, echoing news footage of the Gulf War that sanitises it and eradicates the human factor. The treatment of cadets by the Federation reflects the American administration’s post-Cold War attitude that they can now probably get away with anything, as there are fewer powerful bodies to prevent them (the nadir of which would end up being Bush’s 21st century Gulf War that was in direct violation of the United Nations orders).

Of course that war itself was paralleled by Munich (2004) in which an Israeli counter terrorist group sought revenge for the 1972 Olympic murders, just as President Bush invaded Iraq and Afghanistan, supposedly in retaliation for atrocities against America. And on a related note Hostel (2005) shows that news media have made an effort to return the human factor to war, as it mirrors the treatment of prisoners in Abu Grabe and Guantanamo Bay during that second Gulf War, but does not bode well for American perceptions of the Bush administration. It will be interesting to see how nuclear arms disarmament unfolds during the Obama administration, and how it will be reflected on film.

THE VALIDITY OF FILM

Of course by analysing these films we can only consider it to be a reflection of the sense-making practices of people at the time they were made in relation to events of the past or present, rather than historical document. Nor can we assume that a director’s interpretation of his film or his perception of the times is the ‘correct, and the most important one’.[14] Adopting a post-structuralist approach then, perhaps film should be perceived as a record of fears and desires of societies or governments rather than of events, as there are always alternative interpretations to be had.

For example, The Green Berets is more a reflection of the United States fear of losing the media war after the Tet offensive and a desire to recruit more soldiers during an election year, than it is an accurate account of events in Vietnam.

Of course by analysing these films we can only consider it to be a reflection of the sense-making practices of people at the time they were made in relation to events of the past or present, rather than historical document. Nor can we assume that a director’s interpretation of his film or his perception of the times is the ‘correct, and the most important one’.[14] Adopting a post-structuralist approach then, perhaps film should be perceived as a record of fears and desires of societies or governments rather than of events, as there are always alternative interpretations to be had.

For example, The Green Berets is more a reflection of the United States fear of losing the media war after the Tet offensive and a desire to recruit more soldiers during an election year, than it is an accurate account of events in Vietnam.

|

However that does not necessarily make it an accurate account of those motives either, as they are open to interpretation and conjecture, as well as other, contradictory, meanings that can also be derived from them.

Instead, film should be viewed as an opportunity to ask questions about ‘the meaning of the past’[15] and act as a forum for historical discussion, rather than a direct understanding of history ‘in which people obtain as much of their (knowledge)’, as Robert Brent warns, ‘from watching films and videos as from reading books or sitting in a class room’.[16] |

[14] Alan McKee, Textual Analysis, page 67.

[15] Robert A. Rosenstone, Revisioning History, page 213. [16] Robert Brent, Toplin, 1991. |

Before You Go...

While many movies excel at delivering to us representations of our fears of war on a metaphorical level, many that try to recreate actual historical events are plagued with issues of demonstarting reality through the prism of entertainment. Our next article may be of interest to those wanting to explore this matter further:

From Factual To Fantastic: Issues Of Using Non-Fiction Elements Within Fictional Contexts In Popular Film

Also Worth Checking Out

While many movies excel at delivering to us representations of our fears of war on a metaphorical level, many that try to recreate actual historical events are plagued with issues of demonstarting reality through the prism of entertainment. Our next article may be of interest to those wanting to explore this matter further:

From Factual To Fantastic: Issues Of Using Non-Fiction Elements Within Fictional Contexts In Popular Film

Also Worth Checking Out

|

|