Review of George A. Romero Film Land Of The Dead

|

|

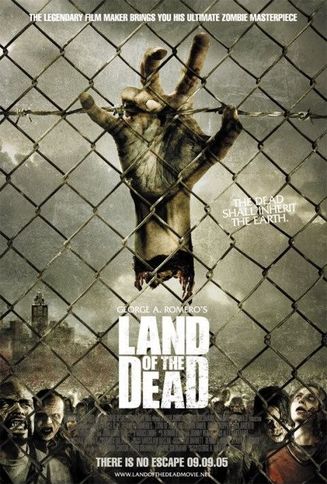

LAND OF THE DEAD (2005)

ZOMBIES NEED FLESHING OUT

By Tom Clare

Land of the Dead (2005)

Directed by George A. Romero. USA: 18.

Whilst George A. Romero’s Living Dead series has forever been associated with lengthy interludes, the wait for Land of the Dead (LOTD) was more pronounced than most. A twenty year zombie hiatus, protracted by the scarcity of other Romero projects (and a period in which he would direct only three feature-length pictures), meant LOTD felt as much a rebirth of its iconic director’s career as for the series itself. The film marks an assured return to the genre he helped define, though by walking a path well-trodden in Romero’s absence, LOTD struggles to distinguish itself from the massing hoards of zombie films vying for the viewers’ attention.

Riley (Simon Baker) has recently retired from his duties patrolling the outskirts of the enclosed, safe-haven known as Fiddler’s Green, where he would busy himself exterminating zombies in a manner that’s as straight-laced and ‘good’ as such a role permits. His wish is to take the armoured vehicle ‘Dead Reckoning’, and head ‘north’ where, just as in 99% of zombie (and indeed more broadly, post-apocalyptic) yarns, the lead protagonist’s motivation lies in the fragile dream of finding an unlikely utopia, hidden within the mass carnage of reality.

The premise shows some thought. The sweeping zombie pandemic last seen in Day of the Dead (1985) has evolved into a reality whereby zombies occupy the vast majority of the urban landscape. Yet what remains of the human populous has for the first time in the series, settled into something that passes for a stable existence, within the social microcosm that is Fiddler’s Green. The rich, white middle-class suits, led by the slithery Kaufman (Dennis Hopper), live the literal and metaphorical ‘high life’, looking down on all from the grander apartments of the tower block, whilst Romero’s nod towards America’s burgeoning rich-poor divide is smartly expressed through the lack of middle ground between those living in luxury and the street dwellers surviving in squalor.

Land of the Dead (2005)

Directed by George A. Romero. USA: 18.

Whilst George A. Romero’s Living Dead series has forever been associated with lengthy interludes, the wait for Land of the Dead (LOTD) was more pronounced than most. A twenty year zombie hiatus, protracted by the scarcity of other Romero projects (and a period in which he would direct only three feature-length pictures), meant LOTD felt as much a rebirth of its iconic director’s career as for the series itself. The film marks an assured return to the genre he helped define, though by walking a path well-trodden in Romero’s absence, LOTD struggles to distinguish itself from the massing hoards of zombie films vying for the viewers’ attention.

Riley (Simon Baker) has recently retired from his duties patrolling the outskirts of the enclosed, safe-haven known as Fiddler’s Green, where he would busy himself exterminating zombies in a manner that’s as straight-laced and ‘good’ as such a role permits. His wish is to take the armoured vehicle ‘Dead Reckoning’, and head ‘north’ where, just as in 99% of zombie (and indeed more broadly, post-apocalyptic) yarns, the lead protagonist’s motivation lies in the fragile dream of finding an unlikely utopia, hidden within the mass carnage of reality.

The premise shows some thought. The sweeping zombie pandemic last seen in Day of the Dead (1985) has evolved into a reality whereby zombies occupy the vast majority of the urban landscape. Yet what remains of the human populous has for the first time in the series, settled into something that passes for a stable existence, within the social microcosm that is Fiddler’s Green. The rich, white middle-class suits, led by the slithery Kaufman (Dennis Hopper), live the literal and metaphorical ‘high life’, looking down on all from the grander apartments of the tower block, whilst Romero’s nod towards America’s burgeoning rich-poor divide is smartly expressed through the lack of middle ground between those living in luxury and the street dwellers surviving in squalor.

|

|

Those familiar with Romero’s powerful expressions of racial inequality highlighted in the unforgettable close of Night of the Living Dead (1968) and the early exchanges of Dawn of the Dead (1978) will recognise the glass-ceiling he creates, limiting blacks to the role of servitude and painting Hispanics as disposable, mercenaries for hire. The black zombie known as ‘Big Daddy’ (Eugene Clark) tentatively challenges such notions however, hinting at a heightened awareness and a grasp of his former life as a mechanic. However, as a revolutionary figure, Big Daddy is ultimately unconvincing.

The film takes a stab at pursuing Day of the Dead’s thought-provoking sub-plot of zombie domestication, though it’s continuation in LOTD doesn’t fit so well. Periodically phasing between behavioural extremes that see Big Daddy either uncommonly benign or excessively furious, it is unclear whether such schizophrenic behaviour and rapid cognitive evolution (expressed in his ability to pick up and use weaponry) offers despair or hope to the human race as, much like the ending itself, it’s rather inconclusive in the final reckoning. With little explanation as to his development, the character threatens to drag the film out of its comfort zone, as when zombies start to act like humans, the action reverts to rather more standard fare.

The film takes a stab at pursuing Day of the Dead’s thought-provoking sub-plot of zombie domestication, though it’s continuation in LOTD doesn’t fit so well. Periodically phasing between behavioural extremes that see Big Daddy either uncommonly benign or excessively furious, it is unclear whether such schizophrenic behaviour and rapid cognitive evolution (expressed in his ability to pick up and use weaponry) offers despair or hope to the human race as, much like the ending itself, it’s rather inconclusive in the final reckoning. With little explanation as to his development, the character threatens to drag the film out of its comfort zone, as when zombies start to act like humans, the action reverts to rather more standard fare.

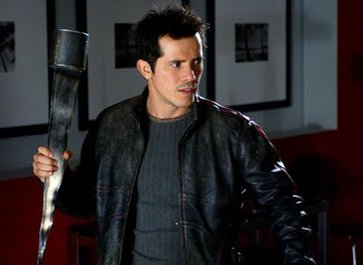

Along the way Riley meets a hive of characters compliant with some rather unflattering stereotypes; hard-ass eye-candy Slack (Asia Argento); neurotic gun-nut Charlie (Robert Joy) and mercenary antagonist, hothead-for-hire Mexican Cholo (John Leguizamo). It’s not that the rag-tag bunch of cohorts and villains are especially dislikeable, it’s just they’re never more than their packaging implies, and Leguizamo in particular is wasted. It’s more direct a shoot-em-up film than any of its predecessors, which modern action fans will no doubt appreciate, but more considered pacing may ultimately have helped flesh out the cast. After all, the attritional, fraught period of self-incarceration within the confines of the mall in Dawn of the Dead not only gave us reason to care for those involved, but also helped set the stage for a suspenseful, do-or-die finale.

|

|

But as it is, there are a few too many loose ends. The ending is thoroughly anti-climactic, suggesting Land of the Dead was leading on to a wider narrative ark to be concluded in later films, only to be ditched in favour of a low-fi series reboot with Diary of the Dead (2007). The lack of focus around the development of the zombies is also odd, and there’s the occasional scene that seemingly doesn’t lead anywhere. One in particular sees Cholo attempting to contain a zombie outbreak in an apartment, but despite what’s implied at the time, the sequence doesn’t ultimately serve any purpose, save possibly to highlight the character’s uncompromising attitude, something that is made clear in every sequence he’s featured in anyway.

Land Of The Dead remains an enjoyable watch, easily surpassing the tacky military-meets-zombie antics of Resident Evil: Apocalypse (2004), a series well-versed in Romero mimicry. The music is decent and the lighting smart enough to lend an ominous, nervy edge to even the most sanitised of locales, whilst all of the conventional scares are pulled off with gusto, if not any great sense of originality. Despite the director’s enduring knack for highlighting contemporary issues, you’re left with the slightly deflating feeling that for the first time, the Living Dead ark doesn’t seem to break any ground. It’s better than your average zombie horror, though perhaps tellingly, someway short of your average Romero.

Land Of The Dead remains an enjoyable watch, easily surpassing the tacky military-meets-zombie antics of Resident Evil: Apocalypse (2004), a series well-versed in Romero mimicry. The music is decent and the lighting smart enough to lend an ominous, nervy edge to even the most sanitised of locales, whilst all of the conventional scares are pulled off with gusto, if not any great sense of originality. Despite the director’s enduring knack for highlighting contemporary issues, you’re left with the slightly deflating feeling that for the first time, the Living Dead ark doesn’t seem to break any ground. It’s better than your average zombie horror, though perhaps tellingly, someway short of your average Romero.

|

|

|

|

|

|