How The Holocaust Is Reflected In The Films Of Director Stanley Kubrick

|

|

CRM 114: Kubrick's Holocaust

HOW THE HOLOCAUST IS REFLECTED IN THE WORK OF CINEMA'S GREATEST MASTER

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts

'CAUSE I’M A NORMAL GUY'[1]:

INTRODUCING STANLEY KUBRICK

American film director Stanley Kubrick is considered one of the most influential of the twentieth century. Famed for perfectionism, he sometimes spent years making a single film. He used his meticulous attention to detail on cinematography, mis-en-scene, editing and colour to express well educated and informed views on technology, family, war, sex, art and a plethora of concerns of his era.

Besides interests in chess, boxing, ballet, Napoleon and the 18th century, he also held fascination with darker matters such as nuclear war, race and the Holocaust. All these interests were expressed by utilising groundbreaking camera work that involved depth of field photography, zooms, tracking and steadicam shots, as well as a unique use of classical and electronic music.

This article explores how he used the theme of the Holocaust in his films by considering the elements above, as well as many others.

As an examination of his work as a director of feature films, it excludes his earlier work and any films made posthumously, such as AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001). Therefore we are concerned with a body of work that consists of 13 films by Kubrick, although admittedly his first feature, Fear and Desire (1953), is overlooked due to its unavailability.

According to the Oxford Dictionary the word ‘Holocaust’ refers to 'The mass killings of Jews by the Nazi regime during World War II'. However for the purposes of this assignment it has been expanded to include the overall Nazi persecution of Jews throughout their reign.

Kubrick’s desire for making films that include the Holocaust as a theme likely lay in his fear of history repeating. This would clearly be a rational fear for any Jew post WWII, but for a film-maker famous for being indirect, it is entirely possible that it may also be a reflection of his more immediate fear of atomic power. 'At one point he said he wanted to go live in Australia,' said David Vaughan, choreographer on Killer’s Kiss (1955), 'because that was the place least likely to be the victim of an atomic bomb attack'.[2] In subsequent films he would draw links between the two.

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts

'CAUSE I’M A NORMAL GUY'[1]:

INTRODUCING STANLEY KUBRICK

American film director Stanley Kubrick is considered one of the most influential of the twentieth century. Famed for perfectionism, he sometimes spent years making a single film. He used his meticulous attention to detail on cinematography, mis-en-scene, editing and colour to express well educated and informed views on technology, family, war, sex, art and a plethora of concerns of his era.

Besides interests in chess, boxing, ballet, Napoleon and the 18th century, he also held fascination with darker matters such as nuclear war, race and the Holocaust. All these interests were expressed by utilising groundbreaking camera work that involved depth of field photography, zooms, tracking and steadicam shots, as well as a unique use of classical and electronic music.

This article explores how he used the theme of the Holocaust in his films by considering the elements above, as well as many others.

As an examination of his work as a director of feature films, it excludes his earlier work and any films made posthumously, such as AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001). Therefore we are concerned with a body of work that consists of 13 films by Kubrick, although admittedly his first feature, Fear and Desire (1953), is overlooked due to its unavailability.

According to the Oxford Dictionary the word ‘Holocaust’ refers to 'The mass killings of Jews by the Nazi regime during World War II'. However for the purposes of this assignment it has been expanded to include the overall Nazi persecution of Jews throughout their reign.

Kubrick’s desire for making films that include the Holocaust as a theme likely lay in his fear of history repeating. This would clearly be a rational fear for any Jew post WWII, but for a film-maker famous for being indirect, it is entirely possible that it may also be a reflection of his more immediate fear of atomic power. 'At one point he said he wanted to go live in Australia,' said David Vaughan, choreographer on Killer’s Kiss (1955), 'because that was the place least likely to be the victim of an atomic bomb attack'.[2] In subsequent films he would draw links between the two.

The Shining (1980). 42 is the number of evil. Lets put it on a kids t-shirt!

'REAL HORROR-SHOW LIKE'[3]:

IMAGES OF THE HOLOCAUST

For whatever reason Kubrick wanted to feature the Holocaust, its presence is made in all of his films. On the surface there are the simple visual references such as the Luger pistol in Killer’s Kiss, the Nazi costumes worn by Billy boy’s gang in A Clockwork Orange (1971), and the saluting of Lolita and Dr Strangelove in the eponymous films Lolita (1962) and Dr Strangelove (1964). However there is also imagery that is slightly less obvious such as the huts that resemble the entrance to Auschwitz in Spartacus (1960), the head-shaving of Full Metal Jacket (1987) and the chalet complex run by an Italian named Patsy and prominently displaying the advertisement sign 'Triumph' (A possible reference to Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935)) that looks like a concentration camp in The Killing (1956).

And then there is the symbolic imagery, such as the number 42, which is used as a numerical representation of the Holocaust (Danger occurs on 42nd Street in Killer’s Kiss, and more subtly Room 237 in The Shining (1980), (2x3x7 = 42)). It is likely Kubrick used this number as it is the year that the Final Solution commenced, but also because 42 is 'a multiple of the number 7'[4], which Kubrick viewed as a symbol of military organisation and evil (Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door).

One of his most striking visuals of the Holocaust is the use of mannequins in noir thriller, Killer’s Kiss. Naked, missing limbs and vulnerable, they would make appearances in his other films, signifying that the viewer has entered the expressionistic version of the world of 1942.

But Kubrick doesn’t limit himself to visuals, as images are also portrayed through the dialogue.

In The Killing Kubrick seems to be echoing conversations of contemporary 1950’s American Jews, as his characters use a plethora of Holocaust terminology. Showing concern for a father figure, (another Kubrick theme), lying on a bed, Johnny Clay asks him to “Stay away from the track”, referring to a race track which in Holocaust jargon could also be interpreted as a train track. A similar scene about trains also appears in Lolita between Humbert and Charlotte, but with malice rather than affection.

Gang members in The Killing also use terms such as 'Grand design', 'Operation' and 'The final preparations' to refer to their plan, highlighting the organisation involved in such a ploy, while drawing parallels with the Nazi ‘Final Solution’.

Sniper-man Nicky, later identified as a racist by yelling 'Nigger' at a parking attendant, talks of taking 'care of a whole room full of people' with a gun that could 'kill ‘em all' despite no such requirements in the plot of the film. His view of killing horses as 'not murder' reverberates the fact that millions of Jews were treated as work horses in slave labour camps, and he is unperturbed by the fact that the horses will 'pile up' on top of one another as Jews did in gas chambers (And also the gang members as they are massacred at the end of the film).

Aside from the terminology, language is also used in a more tongue-in-cheek fashion. George’s blonde wife, seen earlier in the film backlit by a window that contains a swastika pattern, describes a woman he saw on a train as 'A little senile' but makes it sound as though she is saying 'A little Semite'. She then goes on to say things, with a complete indifference, that suggest the train was intended for a concentration camp, 'She was about my age you said. Maybe she was when you started telling this story, but not now' and 'Why talk about it, maybe it is all too good in the long run'. She ends the berating conversation with her poor husband by telling him to make sure he gets the address correct for the 'North Pole', perhaps alluding to the horrors that occurred in Poland.

Taking into consideration Kubrick’s meticulous nature, it seems highly improbable that this use of language is unintentional, especially since much of these dialogue sequences make very little sense, or further the plot, without a deeper interpretation behind them.

IMAGES OF THE HOLOCAUST

For whatever reason Kubrick wanted to feature the Holocaust, its presence is made in all of his films. On the surface there are the simple visual references such as the Luger pistol in Killer’s Kiss, the Nazi costumes worn by Billy boy’s gang in A Clockwork Orange (1971), and the saluting of Lolita and Dr Strangelove in the eponymous films Lolita (1962) and Dr Strangelove (1964). However there is also imagery that is slightly less obvious such as the huts that resemble the entrance to Auschwitz in Spartacus (1960), the head-shaving of Full Metal Jacket (1987) and the chalet complex run by an Italian named Patsy and prominently displaying the advertisement sign 'Triumph' (A possible reference to Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935)) that looks like a concentration camp in The Killing (1956).

And then there is the symbolic imagery, such as the number 42, which is used as a numerical representation of the Holocaust (Danger occurs on 42nd Street in Killer’s Kiss, and more subtly Room 237 in The Shining (1980), (2x3x7 = 42)). It is likely Kubrick used this number as it is the year that the Final Solution commenced, but also because 42 is 'a multiple of the number 7'[4], which Kubrick viewed as a symbol of military organisation and evil (Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door).

One of his most striking visuals of the Holocaust is the use of mannequins in noir thriller, Killer’s Kiss. Naked, missing limbs and vulnerable, they would make appearances in his other films, signifying that the viewer has entered the expressionistic version of the world of 1942.

But Kubrick doesn’t limit himself to visuals, as images are also portrayed through the dialogue.

In The Killing Kubrick seems to be echoing conversations of contemporary 1950’s American Jews, as his characters use a plethora of Holocaust terminology. Showing concern for a father figure, (another Kubrick theme), lying on a bed, Johnny Clay asks him to “Stay away from the track”, referring to a race track which in Holocaust jargon could also be interpreted as a train track. A similar scene about trains also appears in Lolita between Humbert and Charlotte, but with malice rather than affection.

Gang members in The Killing also use terms such as 'Grand design', 'Operation' and 'The final preparations' to refer to their plan, highlighting the organisation involved in such a ploy, while drawing parallels with the Nazi ‘Final Solution’.

Sniper-man Nicky, later identified as a racist by yelling 'Nigger' at a parking attendant, talks of taking 'care of a whole room full of people' with a gun that could 'kill ‘em all' despite no such requirements in the plot of the film. His view of killing horses as 'not murder' reverberates the fact that millions of Jews were treated as work horses in slave labour camps, and he is unperturbed by the fact that the horses will 'pile up' on top of one another as Jews did in gas chambers (And also the gang members as they are massacred at the end of the film).

Aside from the terminology, language is also used in a more tongue-in-cheek fashion. George’s blonde wife, seen earlier in the film backlit by a window that contains a swastika pattern, describes a woman he saw on a train as 'A little senile' but makes it sound as though she is saying 'A little Semite'. She then goes on to say things, with a complete indifference, that suggest the train was intended for a concentration camp, 'She was about my age you said. Maybe she was when you started telling this story, but not now' and 'Why talk about it, maybe it is all too good in the long run'. She ends the berating conversation with her poor husband by telling him to make sure he gets the address correct for the 'North Pole', perhaps alluding to the horrors that occurred in Poland.

Taking into consideration Kubrick’s meticulous nature, it seems highly improbable that this use of language is unintentional, especially since much of these dialogue sequences make very little sense, or further the plot, without a deeper interpretation behind them.

|

|

'IN A WORLD OF SHIT'[5]:

EXPERIENCING THE HOLOCAUST

Kubrick once made a film where 'The age of the dictator was at hand' and a fascist society displayed its power by the symbol of an eagle, saluting, and the neo-classical style of their buildings. Their military system operated as an effective fighting machine and its leaders referred to an oppressed people as an infection that has 'Spread throughout half the empire', while a dictator (Who has broken swastikas on his drapes) talks of 'The new order', 'Enemies of the state', 'Lists of the disloyal' and orders his opponent’s body 'To be burnt and his ashes scattered in secret'.

Casting Romans as Nazis and Slaves as Jews, Spartacus is Kubrick’s non-linear theme-park ride of the Holocaust. We experience the journey of a people, their children included, who just 'Want to get out of this country. We’re marching South' as though they are looking for Israel. We witness their treatment at the hands of the Romans, who inspect their teeth, (Facial inspections were also carried out by the Nazis in Eastern Europe to determine the Jewishness of people), and brandish them with hot irons (Although historically there is no evidence to support that the Romans did this, the Nazis certainly did, tattooing their captives).

We sit inside a hut that resembles a cattle train, as Spartacus awaits his call into the gladiatorial arena, a black man sat opposite him as a reminder that this is a place where race matters. The arena itself asks the viewer to feel the unavoidable repetition of history as it resembles a train track on its side, destined to go around and around in a loop for eternity. While women are forced to undress, men are made to work in a quarry worthy of Mauthausen.

A tracking shot of bodies after a battle shows the climactic horror of the Holocaust, a Roman telling his superior that 'We haven’t made the final count' as though it were the Final Solution. Shots of crowds as Spartacus gives his speech on the mountainside reinforce the scale of people involved in the Holocaust, as does a Roman senator who complains that 'each day the slaves are free swells their number'. However he pronounces 'Swells' as 'Twelve’s', possibly a reference to the 12,000 a day that were liquidated at Auschwitz.

If Spartacus is a theme park ride for the conscious mind, then The Shining is a rave for the unconscious. It is presented as 'a dream, in which the smallest details…linked with other symbols, represent the most dreaded – and consequently most repressed – subject'[6] of the mind (Geoffrey Cocks, Wolf at the Door). Like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) it is a film to be experienced viscerally, but through a much more sinister star-gate. It creates a feeling of the Holocaust without ever referencing it directly or using a narrative allegory (Other than the loosely based American-Indian parable, itself alluded to in a dream-like way).

EXPERIENCING THE HOLOCAUST

Kubrick once made a film where 'The age of the dictator was at hand' and a fascist society displayed its power by the symbol of an eagle, saluting, and the neo-classical style of their buildings. Their military system operated as an effective fighting machine and its leaders referred to an oppressed people as an infection that has 'Spread throughout half the empire', while a dictator (Who has broken swastikas on his drapes) talks of 'The new order', 'Enemies of the state', 'Lists of the disloyal' and orders his opponent’s body 'To be burnt and his ashes scattered in secret'.

Casting Romans as Nazis and Slaves as Jews, Spartacus is Kubrick’s non-linear theme-park ride of the Holocaust. We experience the journey of a people, their children included, who just 'Want to get out of this country. We’re marching South' as though they are looking for Israel. We witness their treatment at the hands of the Romans, who inspect their teeth, (Facial inspections were also carried out by the Nazis in Eastern Europe to determine the Jewishness of people), and brandish them with hot irons (Although historically there is no evidence to support that the Romans did this, the Nazis certainly did, tattooing their captives).

We sit inside a hut that resembles a cattle train, as Spartacus awaits his call into the gladiatorial arena, a black man sat opposite him as a reminder that this is a place where race matters. The arena itself asks the viewer to feel the unavoidable repetition of history as it resembles a train track on its side, destined to go around and around in a loop for eternity. While women are forced to undress, men are made to work in a quarry worthy of Mauthausen.

A tracking shot of bodies after a battle shows the climactic horror of the Holocaust, a Roman telling his superior that 'We haven’t made the final count' as though it were the Final Solution. Shots of crowds as Spartacus gives his speech on the mountainside reinforce the scale of people involved in the Holocaust, as does a Roman senator who complains that 'each day the slaves are free swells their number'. However he pronounces 'Swells' as 'Twelve’s', possibly a reference to the 12,000 a day that were liquidated at Auschwitz.

If Spartacus is a theme park ride for the conscious mind, then The Shining is a rave for the unconscious. It is presented as 'a dream, in which the smallest details…linked with other symbols, represent the most dreaded – and consequently most repressed – subject'[6] of the mind (Geoffrey Cocks, Wolf at the Door). Like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) it is a film to be experienced viscerally, but through a much more sinister star-gate. It creates a feeling of the Holocaust without ever referencing it directly or using a narrative allegory (Other than the loosely based American-Indian parable, itself alluded to in a dream-like way).

|

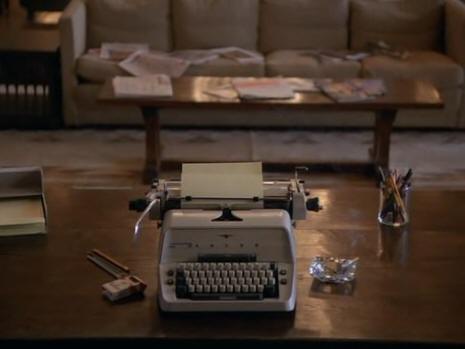

Examples of this are the use of a Volkswagen car, an Adler typewriter and Marlboro cigarettes. The Volkswagen has a history closely linked with Hitler (The style of the Overlook also resembles Hitler’s Berchtesgaden retreat), while the typewriter was instrumental in the bureaucracy necessary for the Holocaust to be executed. Marlboro cigarettes are associated with an advertising campaign that is a symbol of white masculinity in America.

By using these objects Kubrick is using the audience’s memory of Nazi Germany and perceptions of asserting power with masculinity to interpret events in the film. So, for example a scene that zooms out from the typewriter on a neatly organised desk, (With Nazi-style efficiency), that contains little action other than the sound of a ball repetitiously thudding a wall, manages to provoke a sense of the Holocaust without an oppressed person in sight. The selection of objects in alliance with the repetitious sound made by the ball has linked a horror of the past with the inevitability of a horror in the future. The typewriter would be echoed years later by a blue Mercedes in Eyes Wide Shut (1999). |

[1] Clare Quilty, Lolita (1962)

[2] Vincent LoBrutto, Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (New York: Da Capo, 1997), p.93 [3] Alex DeLarge, A Clockwork Orange, (1971) [4] Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door, (Lang, 2004), p87 [5] Private Joker, Full Metal Jacket, (1987) [6] Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door, (Lang, 2004), p220 |

|

|

Another method used in creating this mood is with the many signs in the hotel, which 'represent the strict but permeable apparatus of repression'[7] (Geoffrey Cocks, Wolf at the Door). 'Put Cups and Other Rubbish in the Bins Provided' appears twice, 'Keep This Area Clean' is seen three times and various other signs such as 'Have You Got Your Requisition for Tomorrow' also adorn the walls of the Overlook.

Such a large public space as the Overlook without any people there also adds to the sense of Holocaust, as we feel that people are missing from the scene, as though they have been evicted. Disturbingly, while walking down a corridor lined with pipes (An association of gassing), Mr Ullman says 'By 5 o’clock tonight you’ll never know anyone was here'. The association is furthered later on when Wendy flicks a switch in the boiler room and hears a scream.

In usual Kubrick fashion colour is used to maximum effect, as the red snow-cat and red blood that flows from the elevator signify 'recall, warning, and prediction'[8] of what has occurred in the past and what is going to happen again at the Overlook. The blue of 'natural, emotional, and hierarchical cold' turns Jack’s Adler typewriter into 'a symbol of deadly service to the cold hierarchy of the hotel'.[9] Meanwhile a staining yellow advocaat, (Not-so-coincidentally also the Dutch word for lawyer, which is a profession commonly associated with Jews), conjures up images of 'vermin and disease'[10] that the Nazis used to apply to Jews (Geoffrey Cocks, Wolf at the Door).

With The Shining, Kubrick made the Holocaust more than an historical reference. He used it as a yardstick for all human evil and suffering, now weaved into the very fabric of our space-time, and irreversible.

'THEY ARE ALL EQUAL NOW'[11]:

HISTORY AS TEACHER

The real discourse of The Shining is that it is not the supernatural that haunts us, but our inseparable link with history. However Kubrick is not just using this to entertain a movie audience with ghostly thrills. He is educating them in the repetition of the past.

Barry Lyndon (1975) is not only remarkable for its depth of field photography under particularly difficult source lighting (The cinematography of which was achieved using candles), but also as a film void of any Holocaust references in the traditional Kubrick style. There are no doppelgangers of Auschwitz or ghosts of evil deeds past, to haunt the characters. This is partly because unlike Paths of Glory (1957) or Spartacus, which are films with Holocaust agendas that just happen to be set in a past time, Barry Lyndon is a conscious attempt at recreating the pace of life in an era before the Holocaust. 'It stands for memory as much as historical fact' says Thomas Allen Nelson in his book Kubrick: Inside a film artist’s maze (2000), 'a dream of order and beauty, not just a period of time; a human artefact, not merely a museum collection of paintings'[12].

But this does not mean Kubrick has forgotten the Holocaust. In fact, it is a prequel to it. By recreating the last half of the eighteenth century, Kubrick is able to show us the origins of the Holocaust by witnessing the conditions of a Europe that would allow the creation of Hitler. The Prussian military machine (Which bears a black eagle on its flag) that 'was composed, for the most part, of men from the lowest levels of humanity' is 'considerably worse than the English' and 'Punishment was incessant, and every officer had the right to inflict it' even by 'Mutilation or death', demonstrates a tradition of brutal discipline in the Germanic military mentality.

The burning of farmhouses, and forced marching of workers, foreshadows operation Barbarossa, while Barry’s plan 'to make for Holland' in deserting is testament to the neutrality of the country, even if it is on his way there that he is stopped by the Prussians and asked to produce identity papers (A hint of the possibilities identification documents produced en mass would bring). Even Barry’s assignment to the police force after the war would be echoed by many former SS camp guards after the Second World War. Unlike his other films this is not a metaphor for history, but an earlier cycle.

Just as the brutality of the Holocaust was on a much larger scale than the brutality of the Prussians in Barry Lyndon, Dr Strangelove asks an awkward question about the scale of the next one.

General Turgidson talks of the deaths of '10 to 20 million – tops'. Highlighted by the fact that President Muffley doesn’t want to 'go down in history as the greatest mass murderer since Adolf Hitler', the film making a rare comment in the Kubrick canon, as it overtly references the Holocaust and makes no secret that he is drawing parallels with nuclear armament. But the holocaust proposed in this film is not just a threat to the Jewish community, but to all 'regardless of race, colour or creed' (Bomber pilot Kong).

The CRM 114 is a device Kubrick uses to indicate the programming of minds in order to satisfy the needs of State control. It is represented in Dr Strangelove as a code receiver, comically 'designed not to receive at all', and more literally as a serum forcing Alex to conform to non-violence in A Clockwork Orange. According to Dr Strangelove it 'rules out human meddling' of the individual and allows the State to control the full spectrum of human will to make men into Ubermensch, or the very opposite as would be the case for Alex. It is Kubrick’s observation that neither end well.

The history lesson of Dr Strangelove and Barry Lyndon then, is of repetition and technology ultimately leading to Holocaust. It is fitting that Mandrake, a man who has experienced history before, by being interned at a prisoner of war camp, is the only one who possesses the recall codes (the ability to stop it), but is thwarted first by the ignorance of Lt. Bat Guano, ('What kinda suit is that?') and then by technology (first the telephone and then the HAL-like determination of the CRM). According to Kubrick, human beings have become slaves to systems, just as the Jews were controlled by the concentration camp system.

Was it not in Dr Strangelove (1964) that Matt LeBlanc said 'This Cold War just got hot!'

'STOP, DAVE. I’M AFRAID'[13]:

KUBRICK’S SS

Kubrick never claims to have the answers to prevent another holocaust in his films, but he does try to understand the problem better by examining the perpetrators of them.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey he makes a connection between play and violence with an upward tilting shot of an ape learning to smash bones while the carcass he is beating is made to resemble a xylophone. Although he links this to the Germans by the music playing over the soundtrack it is as more of an explanation of how a cultured people could commit such crimes as the Holocaust, rather than a blaming. If anything, he blames technology, which is constantly distorting perspectives and distancing humans from one another.

One scene in particular seems to have overtones of the SS, as Dr Floyd and his colleagues travel to the moon in a cool rational blue compartment on board a space shuttle. Ahead of them the entrance to the red cockpit resembles a deaths head as they discuss their artificial sandwiches and another, enigmatic subject - 'The way we see it, it’s our job to do this thing the way you want it done and we’re only too happy to oblige' which sounds like they have overdosed on CRM 114 and intend to do something unsavoury in a pit on the moon (which later echoes with ghostly voices singing, the monolith a tombstone to the pit’s open grave, the scale of which can only be found on earth in places such as Babi Yar). The SS image is made all the more likely as they wear eagles on their uniforms and have a cover story about an epidemic, which was often given as the cause of death for thousands during the Einsatzgruppen era.

A similar scene occurs in Full Metal Jacket when American soldiers, sat in their bunks in Vietnam, discuss death in terms of numbers rather than people, and make racist comments. Private Joker says 'I ain’t heard a shot fired in anger in weeks', as though they were running a concentration camp where the thrill of the kill had been superseded by the gas chambers (The ‘thrill’ being of particular importance to a group of men who have substituted sex for violence). Later on in the film they walk past a pillar that resembles the entrance to Heinrich Himmler’s SS ritual Castle. And although Kubrick denies it is intentional, can there be any wonder why there is a burning Monolith in the last section of such a film?

'FUCK'[14]:

IN CONCLUSION

As most of Kubrick’s films have such an indirect discourse on the matter of the Holocaust one could possibly argue that the patterns are just coincidental. However I would argue that they are too frequent to ignore. While perhaps not all his references are intentional, there are still certainly plenty to consider, and they create the overall effect, regardless.

KUBRICK’S SS

Kubrick never claims to have the answers to prevent another holocaust in his films, but he does try to understand the problem better by examining the perpetrators of them.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey he makes a connection between play and violence with an upward tilting shot of an ape learning to smash bones while the carcass he is beating is made to resemble a xylophone. Although he links this to the Germans by the music playing over the soundtrack it is as more of an explanation of how a cultured people could commit such crimes as the Holocaust, rather than a blaming. If anything, he blames technology, which is constantly distorting perspectives and distancing humans from one another.

One scene in particular seems to have overtones of the SS, as Dr Floyd and his colleagues travel to the moon in a cool rational blue compartment on board a space shuttle. Ahead of them the entrance to the red cockpit resembles a deaths head as they discuss their artificial sandwiches and another, enigmatic subject - 'The way we see it, it’s our job to do this thing the way you want it done and we’re only too happy to oblige' which sounds like they have overdosed on CRM 114 and intend to do something unsavoury in a pit on the moon (which later echoes with ghostly voices singing, the monolith a tombstone to the pit’s open grave, the scale of which can only be found on earth in places such as Babi Yar). The SS image is made all the more likely as they wear eagles on their uniforms and have a cover story about an epidemic, which was often given as the cause of death for thousands during the Einsatzgruppen era.

A similar scene occurs in Full Metal Jacket when American soldiers, sat in their bunks in Vietnam, discuss death in terms of numbers rather than people, and make racist comments. Private Joker says 'I ain’t heard a shot fired in anger in weeks', as though they were running a concentration camp where the thrill of the kill had been superseded by the gas chambers (The ‘thrill’ being of particular importance to a group of men who have substituted sex for violence). Later on in the film they walk past a pillar that resembles the entrance to Heinrich Himmler’s SS ritual Castle. And although Kubrick denies it is intentional, can there be any wonder why there is a burning Monolith in the last section of such a film?

'FUCK'[14]:

IN CONCLUSION

As most of Kubrick’s films have such an indirect discourse on the matter of the Holocaust one could possibly argue that the patterns are just coincidental. However I would argue that they are too frequent to ignore. While perhaps not all his references are intentional, there are still certainly plenty to consider, and they create the overall effect, regardless.

|

[7] Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door, (Lang, 2004), p229

[8] Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door (Lang, 2004), p.236 [9] Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door (Lang, 2004), p.236 [10] Geoffrey Cocks, The Wolf at the Door (Lang, 2004), p.244 [11] Epilogue, Barry Lyndon, (1975) [12] Thomas Allen Nelson, Kubrick: Inside a film artist’s maze, (Indiana, 2000), p.177 [13] HAL, 2001: A Space Odyssey, (1968) [14] Alice Harford, Eyes Wide Shut, (1999) |

|

|

By featuring the Holocaust in his films, perhaps he is able to feel like he has some control over it, as he does with his symmetry of shots. But this does not seem to make him delusional about the nature of control, as random events of chance often affect plot in his films (The dog that leads to the suitcase spill in The Killing, for example).

The use of the Holocaust in his films seems to be his way of telling the world that as a part of history the Holocaust is now inescapable. Or more specifically he might be telling it to a Jewish audience, as he may have made his films, arguably, specifically for Jews but gave them a gentile façade in order to make them more commercially viable. This might certainly be the case with his second and final films, both of which indirectly deal with very specific Jewish issues (Killer’s Kiss explores the difficulty of American Jews to identify with the Holocaust, a problem that occurred thousands of miles away, while Eyes Wide Shut addresses the Jewish exclusion from gentile society).

Or perhaps the presence of the Holocaust in his films is just echoing the words of a famous Holocaust survivor who asked 'How can there be art after this?'

The use of the Holocaust in his films seems to be his way of telling the world that as a part of history the Holocaust is now inescapable. Or more specifically he might be telling it to a Jewish audience, as he may have made his films, arguably, specifically for Jews but gave them a gentile façade in order to make them more commercially viable. This might certainly be the case with his second and final films, both of which indirectly deal with very specific Jewish issues (Killer’s Kiss explores the difficulty of American Jews to identify with the Holocaust, a problem that occurred thousands of miles away, while Eyes Wide Shut addresses the Jewish exclusion from gentile society).

Or perhaps the presence of the Holocaust in his films is just echoing the words of a famous Holocaust survivor who asked 'How can there be art after this?'

Before You Go...

While this piece on Kubrick and The Holocaust may have touched upon the theme of Jewish identity, our next article examines it in further detail. Kubrick's final film says much about Jewish identity at the time it was made:

Eyes Wide Shut: Kubrick's Take On Jewish Identity In 20th Century America

Also Worth Checking Out

While this piece on Kubrick and The Holocaust may have touched upon the theme of Jewish identity, our next article examines it in further detail. Kubrick's final film says much about Jewish identity at the time it was made:

Eyes Wide Shut: Kubrick's Take On Jewish Identity In 20th Century America

Also Worth Checking Out

- Wanting even more Kubrick? Then take a look at the Psychosexual Dynamics In Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut

- Interested in further discussions on the Holocaust? Then read Asking Difficult Questions About Nazi Filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl

- Explorations of war and film of interest? Check out How The Fears Of Nuclear War Were Put On Film

|

|