Review of Walter Salles Brazilian Film Central Station

|

|

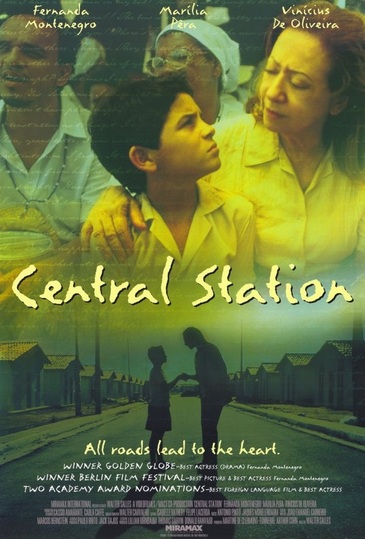

CENTRAL STATION (1998)

SHEER BRAZILIANCE

|

By Tom Clare

Central Station (1998) Directed by Walter Salles. Brazil: 15. In 1990, Brazilians elected a leader for the first time since the early sixties as a new democracy succeeded military rule. The durability of the system would be immediately tested however by financial meltdown, political corruption and presidential impeachment, and as a consequence of inhibitive laws, national film production all but ceased completely. The struggles only galvanised filmmakers however, and as the nation started to recover, its cinema experienced something of a renaissance; giving rise to beautiful, slick-looking films that both embraced and challenged Brazil’s unique though often turbulent culture. Central Station, which arrived in 1998, would prove to be a standout film of its time. Beginning in Rio de Janeiro’s main train station (Central do Brasil, which is the film’s original Portuguese title), the story follows cynical, middle-aged teacher-turned-letter writer Dora (Fernanda Montenegro) who reels off her days penning letters dictated to her by illiterate travellers. It’s established that she’s not much of a people-person (describing home life as having ‘no children, no husband, no family, no dog’) and plays God with peoples communications, deciding each night which letters to post and which to throw away. |

Circumstances bring her and young boy Josué (Vinícius de Oliveira) together, after his mother is run over and killed not far from the station. The two form an unlikely and highly reluctant pairing as they resolve to leave the city in search of the boy’s illusive father, Jesus, in the country’s rural north-east.

Central Station excels in almost every area you could care to judge it. It follows many of director Walter Salles’s well-practiced motifs; a literal and metaphorical journey evoked by road movie elements (1996’s Foreign Land, 2004’s The Motorcycle Diaries); a young, aspiring protagonist battling with difficult circumstances, and a search for the missing father figure. The story is poignant and thought-provoking, the acting almost universally good, the music superb and the cinematography simply breath-taking.

Indeed, it’s one of the best-looking movies you’re ever likely to see, not simply because of the photogenic settings that brim with vitality, impossibly blue-skies and sunny, golden landscapes – it has all of these as well, of course – but because of how cinematographer Walter Carvalho varies lighting, colour and composition to affect meaning. To Dora, Rio’s train station is a familiar yet impersonal environment; it’s all very muted looking. Even her home, which is full of commodities and lights, seems as colourless as her life. Through Josué’s eyes, the station assumes a subtly different atmosphere when he loses his mother; unfocused background lights pool and seep monstrously, whilst the myriad of people who pass through the shots have their features blurred indistinguishably, thus we see a child who is lost, and feels truly isolated despite the bustle.

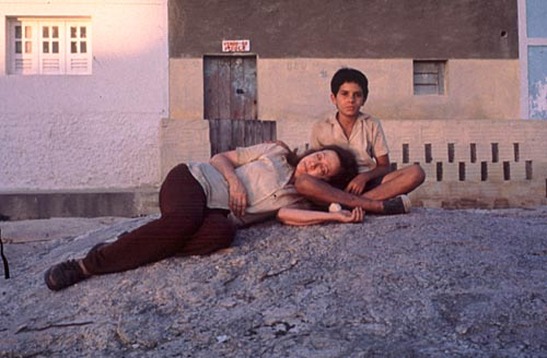

As the pair travel to the Brazilian countryside however, purpose and colour are returned to their lives in tandem. A parallel is drawn between urban and the rural life; emphasising the importance of a culture remaining in touch with its roots and not segregating on geographical terms. It’s more noticeable and yet better handled than in Salles’s other ventures; the sentiment is just right, thanks largely to the main characters and their development upon leaving Rio. Though it’s not a feel-good film in the conventional sense, the implication that escaping the rigours of city life in favour of reconnecting with the outside world is a positive one, even if to some it might seem an overly-idealised viewpoint.

CENTRAL CASTING

It’s arguably the two lead actors who make the film though. Fernanda Montenegro (whose performance won her the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival as well as a Best Actress nod at the Oscars – a first for Brazilian actresses) is tremendous as Dora. Her world-weariness and ruthless ‘look after number one’ approach to life paint her as a rather abrasive figure to begin with, but the thawing of this maternal figure is not the hasty make-over many filmmakers cram into a couple of scenes. The transformation is a gentle one; she is a complex personality who grows from the triumphs as much as she learns from the mishaps that are thrown at her. Central Station is as much a journey for Dora as it is for Josué. Leaving the city is akin to an awakening, as she seeks to exorcise demons left in stasis during her slumberous existence in Rio, and a resilient, selfless side begins to flower. And every step of the way, Montenegro’s performance is virtually flawless.

Central Station excels in almost every area you could care to judge it. It follows many of director Walter Salles’s well-practiced motifs; a literal and metaphorical journey evoked by road movie elements (1996’s Foreign Land, 2004’s The Motorcycle Diaries); a young, aspiring protagonist battling with difficult circumstances, and a search for the missing father figure. The story is poignant and thought-provoking, the acting almost universally good, the music superb and the cinematography simply breath-taking.

Indeed, it’s one of the best-looking movies you’re ever likely to see, not simply because of the photogenic settings that brim with vitality, impossibly blue-skies and sunny, golden landscapes – it has all of these as well, of course – but because of how cinematographer Walter Carvalho varies lighting, colour and composition to affect meaning. To Dora, Rio’s train station is a familiar yet impersonal environment; it’s all very muted looking. Even her home, which is full of commodities and lights, seems as colourless as her life. Through Josué’s eyes, the station assumes a subtly different atmosphere when he loses his mother; unfocused background lights pool and seep monstrously, whilst the myriad of people who pass through the shots have their features blurred indistinguishably, thus we see a child who is lost, and feels truly isolated despite the bustle.

As the pair travel to the Brazilian countryside however, purpose and colour are returned to their lives in tandem. A parallel is drawn between urban and the rural life; emphasising the importance of a culture remaining in touch with its roots and not segregating on geographical terms. It’s more noticeable and yet better handled than in Salles’s other ventures; the sentiment is just right, thanks largely to the main characters and their development upon leaving Rio. Though it’s not a feel-good film in the conventional sense, the implication that escaping the rigours of city life in favour of reconnecting with the outside world is a positive one, even if to some it might seem an overly-idealised viewpoint.

CENTRAL CASTING

It’s arguably the two lead actors who make the film though. Fernanda Montenegro (whose performance won her the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival as well as a Best Actress nod at the Oscars – a first for Brazilian actresses) is tremendous as Dora. Her world-weariness and ruthless ‘look after number one’ approach to life paint her as a rather abrasive figure to begin with, but the thawing of this maternal figure is not the hasty make-over many filmmakers cram into a couple of scenes. The transformation is a gentle one; she is a complex personality who grows from the triumphs as much as she learns from the mishaps that are thrown at her. Central Station is as much a journey for Dora as it is for Josué. Leaving the city is akin to an awakening, as she seeks to exorcise demons left in stasis during her slumberous existence in Rio, and a resilient, selfless side begins to flower. And every step of the way, Montenegro’s performance is virtually flawless.

|

|

|

|

Josué is similarly superb. Child actors can be a gamble to say the least, especially given that Vinícius de Oliveira was previously a shoe-shine boy who had never previously acted (apparently he won the part against 15,000 others who auditioned). Crucially, he and Montenegro form a bond that makes their skilfully woven on-screen dynamic a success. They reflect a mutual abrasiveness to begin with; Dora stubborn in her cynicism, Josué resolute in his absolute conviction that he would find the father he had never met. His hot-headed bluntness (telling Dora during one argument that she needs make-up as she looks ‘like a man’) proves as funny as his reflections with Dora are touching. Central Station tugs at the emotions, but is never overblown or melodramatic, a problem that has filtered into some Brazilian films perhaps due to the prominence of their TV soaps. By the end, it’s almost impossible not to empathise strongly with both characters, leading to a finale which is incredibly moving.

Much of the rest of the cast play only bit-parts, but there are still some good showings. Marília Pêra plays Dora’s friend Irene who lives in the same apartment block in Rio, and is used sparingly to provide lighter moments. A likable, free-spirit, her brief flashes of seriousness serve to jolt Dora’s conscience on occasions when her morals desert her. The beautiful, sweeping musical score deserves a mention also, as though it isn’t necessarily the most striking element in Central Station, the mood of the accompaniment is astutely judged.

Central Station shows snippets of Brazilian life in and around the main story in a manner that seeks to be neither overly sympathetic nor judgemental; it just happens, and this is perhaps a key facet in ensuring the film flowed effectively. You get the good and the bad; beautiful monuments, dizzying carnivals, bustling markets mixed with poverty, broken families and crime. A thief is shot dead at the station in a scene that is a reference to the country’s uncompromising law enforcement, but is filmed in such a neutral fashion that it seems almost like a documentary excerpt. Illiteracy is a problem Salles highlights in both the city and the country, but hints through Dora’s behaviour that the educated middle-classes have power that is regularly abused in the city. Again, this is something designed for the viewer to contemplate; the film never lingers long on such weighty issues.

Intelligent and deep, yet accessible and watchable, Central Station gets just about everything right. Stunning cinematography, engaging characters and a story that brings the Brazil of the screen to life, it’s amazingly accomplished. As films from Latin America go, it’s better than City of God (2002), better than Amores Perros (2000), and must rank among the most fully-realised pieces of cinema you could ever hope to see.

Much of the rest of the cast play only bit-parts, but there are still some good showings. Marília Pêra plays Dora’s friend Irene who lives in the same apartment block in Rio, and is used sparingly to provide lighter moments. A likable, free-spirit, her brief flashes of seriousness serve to jolt Dora’s conscience on occasions when her morals desert her. The beautiful, sweeping musical score deserves a mention also, as though it isn’t necessarily the most striking element in Central Station, the mood of the accompaniment is astutely judged.

Central Station shows snippets of Brazilian life in and around the main story in a manner that seeks to be neither overly sympathetic nor judgemental; it just happens, and this is perhaps a key facet in ensuring the film flowed effectively. You get the good and the bad; beautiful monuments, dizzying carnivals, bustling markets mixed with poverty, broken families and crime. A thief is shot dead at the station in a scene that is a reference to the country’s uncompromising law enforcement, but is filmed in such a neutral fashion that it seems almost like a documentary excerpt. Illiteracy is a problem Salles highlights in both the city and the country, but hints through Dora’s behaviour that the educated middle-classes have power that is regularly abused in the city. Again, this is something designed for the viewer to contemplate; the film never lingers long on such weighty issues.

Intelligent and deep, yet accessible and watchable, Central Station gets just about everything right. Stunning cinematography, engaging characters and a story that brings the Brazil of the screen to life, it’s amazingly accomplished. As films from Latin America go, it’s better than City of God (2002), better than Amores Perros (2000), and must rank among the most fully-realised pieces of cinema you could ever hope to see.

|

|

|

|

|

|