Issues of using Non-Fiction Elements within Fictional Contexts in Popular Film

|

|

FROM FACTUAL TO FANTASTIC

|

ISSUES OF USING NON-FICTION ELEMENTS WITHIN FICTIONAL CONTEXTS IN POPULAR FILM

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts While films of fiction have grossed billions of pounds at the box office, a small percentage of movies have been works of non-fiction. However many have been a curious meld of fiction and non-fiction themes, including the highest earning film of all time, Titanic (1997)[1]. |

James Cameron filmed underwater documentary elements for blockbuster Titanic (1997)

Issues concerning the use of non-fiction in fictional contexts is a minefield. It is particularly controversial in film, with many points to consider. But before the matter can be properly discussed it is crucial that the terms of the question are understood. According to CriticalReading.com (2000) ‘the distinction addresses whether a text discusses the world of the imagination (fiction) or the real world (nonfiction)’ and points out that ‘the test is not whether the assertions are true. Nonfiction can make false assertions, and often does. The question is whether the assertions claim to describe reality, no matter how speculative the discussion may be.’[2]

Considering non-fiction to be a term occasionally covered by the word ‘history’ for the remainder of this article, (on the understanding that history is primarily concerned with non-fiction events), Jerome de Groot (2009, p208) describes that ‘in these films history becomes both a set of reference points – the facts that are or sometimes not known – and an arena simultaneously connected to the present but also conceptually ‘othered’, a place where things happened in the abstract but which might be changed through understanding and reconsideration.’[3]

Considering non-fiction to be a term occasionally covered by the word ‘history’ for the remainder of this article, (on the understanding that history is primarily concerned with non-fiction events), Jerome de Groot (2009, p208) describes that ‘in these films history becomes both a set of reference points – the facts that are or sometimes not known – and an arena simultaneously connected to the present but also conceptually ‘othered’, a place where things happened in the abstract but which might be changed through understanding and reconsideration.’[3]

|

|

|

That is not to suggest that Paul Smith’s point in The Historian and Film (1975, p7) that ‘reality inheres even in a fake: it is a real fake, the result of real events’ because actors actually perform the acts they are projecting and so on is not valid, but it would prove overall too literal and redundant an interpretation for an exploration of the differences between genres. |

[1] According to www.imdb.com.

[2] Parentheses and emphasis in original. [3] The word “othered” appears in the original. |

As G.M. Trevelyan (1945, p21) explains, the main problem of film portraying non-fiction events is that it can only provide ‘bits of past history without bringing the story up to recent and present time’ and therefore omitting much information about the occurrences before and after the subject matter. He argues that to combat this, the filmmakers need a rigorous ‘study of the laws of historical evidence’ and to take into account that a large portion of the audience are unfamiliar with the specifics of the events being represented, as backed up by Smith (1975, p11):

‘Viewers are not well equipped to evaluate it and are unlikely to be reached by any criticism or refutation of it from professional historians; for many of them it will not be an interpretation but a final statement of the truth about its subject, driven home with all the force of visual demonstration. The historian, then, is under some compulsion to do what he can, when invited, to see that the principles of his trade are observed’.

However Smith also suggests this is easier said than done, as ‘there are methodological problems of great complexity here’ as what a film means and contains ‘either for its creators or for any particular audience’ are ‘not simple questions’ to answer.

YESTERDAY IS TODAY

In Big Screen Rome, Cyrino (2005, p2) suggests that ‘these cinematic images influence our contact with “real” artifacts from the ancient past’ and highlights that ‘films about the past elucidate our own society’s present desires, concerns, and fears’.

J.A.S. Grenville (1970, p18), referring to Eisenstein’s formulations on film creation, claims this is due to film banishing ‘the limitations of time and space and the film maker can set out events in the time spaces he desires as he can switch from one geographical location to another’ which in conjunction with the ‘variation of the camera angle, the selectivity and order in which separate scenes are spliced together can create an illusion of reality, though the “reality” has been rearranged to suit the film maker’s artistic, social, or political intentions’. Therefore, ultimately, the interpretation of the film is dependent on ‘the relation between the authors of the film, society and the work.’

‘Viewers are not well equipped to evaluate it and are unlikely to be reached by any criticism or refutation of it from professional historians; for many of them it will not be an interpretation but a final statement of the truth about its subject, driven home with all the force of visual demonstration. The historian, then, is under some compulsion to do what he can, when invited, to see that the principles of his trade are observed’.

However Smith also suggests this is easier said than done, as ‘there are methodological problems of great complexity here’ as what a film means and contains ‘either for its creators or for any particular audience’ are ‘not simple questions’ to answer.

YESTERDAY IS TODAY

In Big Screen Rome, Cyrino (2005, p2) suggests that ‘these cinematic images influence our contact with “real” artifacts from the ancient past’ and highlights that ‘films about the past elucidate our own society’s present desires, concerns, and fears’.

J.A.S. Grenville (1970, p18), referring to Eisenstein’s formulations on film creation, claims this is due to film banishing ‘the limitations of time and space and the film maker can set out events in the time spaces he desires as he can switch from one geographical location to another’ which in conjunction with the ‘variation of the camera angle, the selectivity and order in which separate scenes are spliced together can create an illusion of reality, though the “reality” has been rearranged to suit the film maker’s artistic, social, or political intentions’. Therefore, ultimately, the interpretation of the film is dependent on ‘the relation between the authors of the film, society and the work.’

|

|

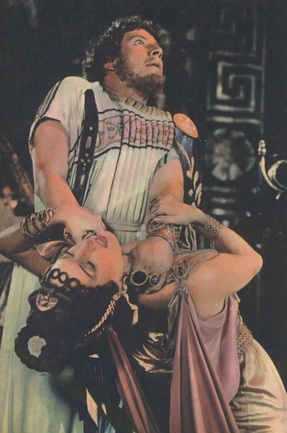

Quo Vadis (1951) Politics really hasn't changed...

Cyrino agrees, not only claiming that these films say more about ‘contemporary, social political issues at the time the films were released’ than it does about the non-fiction elements they portend to illuminate, but applauds their poetic license as it ‘allows people to describe the present time in a free, imaginary way’. Citing Quo Vadis (1951), as an example, she suggests that the film is not simply telling the tale of ancient Romans, but is a reflection of ‘the social and cultural environment of 1950s America and the tense political atmosphere of the Cold War’ (2005, p3). ‘This characterization of the film’s hero as a “Christian soldier” suggests an endorsement of the “peaceful militarism” of the Eisenhower years of the 1950s’ she explains (2005, p29).

In Film as History (1970, p7), Grenville offers that the non-fiction events should be the primary concern of a factually based film, as opposed to a script written for entertainment purposes, which then selects bits of history to include, as the involvement of editing can create entirely different stories even though the same elements are involved[4]. Price (1999, p6) highlights the practical difficulties of doing this however, as ‘when historians attempt to explain an event, the whole of history is greater than the sum of its casual parts; no single identifiable force or combination of forces can account for a historical occurrence’, while the entertainment nature of feature films demands it examines a single event.

In Film as History (1970, p7), Grenville offers that the non-fiction events should be the primary concern of a factually based film, as opposed to a script written for entertainment purposes, which then selects bits of history to include, as the involvement of editing can create entirely different stories even though the same elements are involved[4]. Price (1999, p6) highlights the practical difficulties of doing this however, as ‘when historians attempt to explain an event, the whole of history is greater than the sum of its casual parts; no single identifiable force or combination of forces can account for a historical occurrence’, while the entertainment nature of feature films demands it examines a single event.

|

[4] Grenville was talking specifically about the use of non-fiction film clips in documentary form rather than outright fiction, although the principles seem to apply here too, perhaps even more aptly. An example of this being done is cited on page 8 of his book Film and History (1970), concerning the Berlin Worker’s Film Society and their use of archive footage.

[5] It is appreciated that photographs and film play eyewitness to events also, however they are still placed and operated by people, and omit anything they are not pointed at, failing to capture the context of a situation, as described by Paul Smith in The Historian and Film (1975, p5) and explored further on in the article. |

FROM A DIFFERENT POINT OF VIEW

The matter is further complicated because all accounts of non-fiction originate with people[5], as Grenville (1970, p11), referring to a medieval tapestry asks ‘Did Luttrell Castle really look like this or is the picture an artistically imaginative drawing of a great castle?’ begging the question of who is to say what is the correct interpretation of a non-fiction event? In Consuming History (2009, p209) de Groot insists that although non-fiction occurrences are witnessed by human beings, when they recall the information to another person it becomes instantly corrupted and therefore contaminates its value as factual. Using Downfall (2004) as an example he explains how the use of non-fiction in fiction is factual and yet biased. ‘Downfall, based on the memoirs of Hitler’s secretary Traudle Junge, contributes to the strand of biographical film as well as demonstrating its own subjectivity by being bookended by an interview with Junge in the present day. It is both more truthful and less truthful as a consequence, and this uncertainty and |

desire for both understanding as well as a shying away from difficult wider issues characterise much historical biopics about key ‘evil’ figures’.

|

There appears to be no alternative however, as even when human memory and perception is curtailed and film is used directly as a witness of non-fiction, there are still difficulties, as Paul Smith (1975, p5) explains ‘it is often a relatively trivial and superficial record, capturing only the external appearance of its subjects and offering few insights into the processes and relationships, causes and motives’. Therefore, in film terms, non-fiction can be better understood when used in a fictional context.

Cyrino (2005, p222) explains by using Gladiator (2000) as an example. In an attempt to demonstrate the transitional period of the Roman Empire during the time of the tension between Aurelius and Commodus, the film invents the fictional character and storyline of Maximus, ‘who serves as cinematic catalyst’ between the men and shows the factually concerned issues of the ancient world. |

|

|

The film The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) also portrays this period in history, but uses the fictional character of Livius as the instigator between the men, highlighting Grenville’s point earlier that completely different stories can be created from non-fiction elements, which are at the mercy of the film maker.

Price (1999, p2) argues that historical narrative must ‘not solely concern itself with presenting factual information’ as the non-fiction is largely worthless to an audience in its pure form and that ‘the emotional, psychological and intellectual dimensions that we experience’ in fiction film[6] can help us understand characters motivations. Travelyan (1945, p24) concurs that films need to ‘make us take short cuts to the truth’ and even encourages it as a duty of film makers to ‘make it fascinating as possible, or at any rate not to conceal its fascination under the heap of learning which ought to underlie but not overwhelm written history’. He stresses that it is then the responsibility of the viewer to study the history if they want to learn more, accepting the film as only ‘an enquiry into the value, or rather the values, of history’ (Travelyan, p8).

According to Price (1999, p5) the merging of non-fiction and fiction is crucial to a full understanding of non-fiction in literature:

‘Meaningful histories, histories that can be of use to us, must allow us to sense the past through figurative language. In other words, we must sense the past to make sense of it. The mythic structures, tropes, and varying narrative strategies that one finds in the novels of poietic history became the means by which these novelists allow us to experience the past in the present with an eye toward the future’.

Equally applicable to film, he further argues that this ‘eye to the future’ is the reason audiences show interest in non-fiction within an entertaining framework.

‘…poietic histories are written so as to affect our future, the future of the reading audience… cause us to rethink the past and reconsider what we might plan for our future… a major goal of any poietic history is to reconfigure the past in ways that will help us configure our future’[7]. (Price, p4)

Price (1999, p2) argues that historical narrative must ‘not solely concern itself with presenting factual information’ as the non-fiction is largely worthless to an audience in its pure form and that ‘the emotional, psychological and intellectual dimensions that we experience’ in fiction film[6] can help us understand characters motivations. Travelyan (1945, p24) concurs that films need to ‘make us take short cuts to the truth’ and even encourages it as a duty of film makers to ‘make it fascinating as possible, or at any rate not to conceal its fascination under the heap of learning which ought to underlie but not overwhelm written history’. He stresses that it is then the responsibility of the viewer to study the history if they want to learn more, accepting the film as only ‘an enquiry into the value, or rather the values, of history’ (Travelyan, p8).

According to Price (1999, p5) the merging of non-fiction and fiction is crucial to a full understanding of non-fiction in literature:

‘Meaningful histories, histories that can be of use to us, must allow us to sense the past through figurative language. In other words, we must sense the past to make sense of it. The mythic structures, tropes, and varying narrative strategies that one finds in the novels of poietic history became the means by which these novelists allow us to experience the past in the present with an eye toward the future’.

Equally applicable to film, he further argues that this ‘eye to the future’ is the reason audiences show interest in non-fiction within an entertaining framework.

‘…poietic histories are written so as to affect our future, the future of the reading audience… cause us to rethink the past and reconsider what we might plan for our future… a major goal of any poietic history is to reconfigure the past in ways that will help us configure our future’[7]. (Price, p4)

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, Grenville (1970, p9) makes possibly the most important and yet overlooked point about the use of non-fiction in fiction,

‘The essential and simple point to grasp then is that a piece of film is not some unadulterated reflection of historical truth captured by the camera… the importance to be attached to it depends on the question [we ask][8] of it’.

Ultimately, Grenville (1970, p9) makes possibly the most important and yet overlooked point about the use of non-fiction in fiction,

‘The essential and simple point to grasp then is that a piece of film is not some unadulterated reflection of historical truth captured by the camera… the importance to be attached to it depends on the question [we ask][8] of it’.

|

[6] Price actually talks about literary fiction in this instance, but it equally applies to film.

[7] Emphasis in original. [8] The original states ‘the historian asks’. |

As implied by the statement, popular film is not primary evidence, and so should not be considered with such importance. Film can be useful in understanding non-fiction events, as long it is understood to be an understanding derived more from the time it is produced, about the people it was made for and by, than of the occurrences it indulges in as a subject matter.

Trevelyan claims that ‘there can never be a final “verdict on history”. But at least it is more possible to have an opinion of some value’ now that films provide an arena for wider-public access to history (1945, p23). |

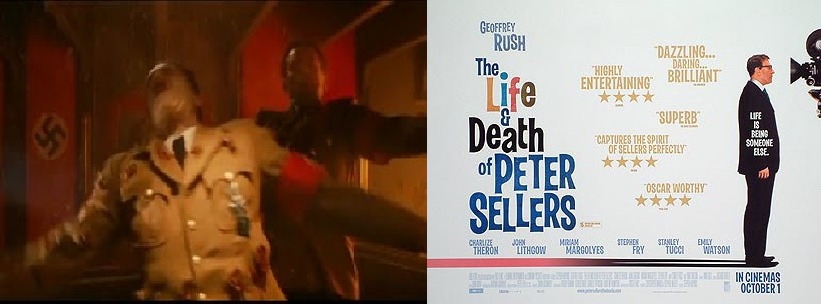

Even with all the complexities involved in using non-fiction in fictional contexts, it continues to be a staple of popular cinema with films such as The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (2004) and Inglorious Basterds (2009) now acknowledging and consciously provoking and ridiculing the difficulties involved, despite not being able to escape them. This is a field of research yet to be as widely explored as some other facets of cinema, and hopefully we just have sign-posted directions for future research on the matter. Let’s hope its interpreted that way in ten years’ time.

Before You Go...

Most historical epics are plagued with historical inaccuracies, and some of our favourites featuring Norsemen are no exception. Our next article takes a look at:

Viking Funerals On Film: Setting Sail On Viking Movie Myths

Also Worth Checking Out

Most historical epics are plagued with historical inaccuracies, and some of our favourites featuring Norsemen are no exception. Our next article takes a look at:

Viking Funerals On Film: Setting Sail On Viking Movie Myths

Also Worth Checking Out

- Brazil's unique and turbulent 90s culture as seen in the film Central Station

- How the drama of nuclear arms development and war was told in movies: The Atomic Age On Film

- Examining the biopic of a child actor's life and death: Who Killed Pixote?

|

|