Avatar: Politics, Plot and Genre of a Science Fiction Epic

|

|

|

The following article is an extract from the book 'The Film Reader's Guide To James Cameron's AVATAR - Understanding how the sci-fi epic reflects its historical and cultural context' by Bryn V. Young-Roberts. Available from Amazon and various other stockists.

|

AVATAR (2009)

'YOU ARE NOT IN KANSAS ANYMORE'

POLITICS, PLOT AND GENRE OF A SCI-FI EPIC

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts

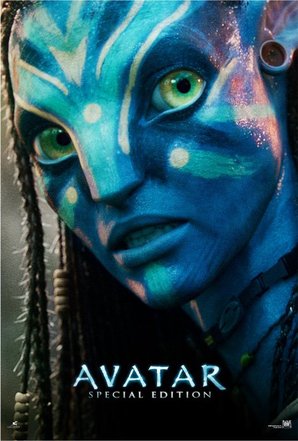

James Cameron’s eighth film, Avatar, was released in December 2009, the same year George W. Bush, the 43rd President of the United States, left office. Within weeks it became the highest grossing film of all time, one notch above Titanic (also a James Cameron film). The plot concerns Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic ex-marine in the 22nd century who joins an anthropological science team on the planet Pandora, and inhabits an avatar (a remote-controlled body) in the form of a member of the native population, the Na’vi, in order to gain military intelligence on them.

Although he performs his duty faithfully, he forms a bond with the Na’vi culture and becomes romantically involved with the daughter of the tribe’s leader, Neytiri (Zoe Saldana), which pits him in opposition to his superiors’ intention to destroy the Na’vi forest homeland in order to mine a valuable substance called Unobtainium.[1] This results in Sully leading the Na’vi in a revolt against the people of his birth nation and overthrowing them, eventually expelling them from Pandora. In the final frames of the film, Sully abandons his human body in a spiritual ceremony that permanently merges his consciousness with his physical Na’vi avatar, therefore completing his transformation into the indigenous culture and society.

In a thinly veiled allegorical parable, Avatar challenges blind submission to authority, both political and economic, while appearing to stand for the virtues of diversity and non-conformity, rebelling against authoritarianism and ethnocentrism. The story has been widely criticised for its clichéd and derivative nature.[2] It is not only similar to the Disney film Pocahontas (dir. Gabriel and Golberg, 1995), but has specific genre roots dating back even further to 1970’s revisionist Westerns (which incidentally is also the decade that Cameron first conceptualised his ideas for Avatar, although a film treatment would not be written until 1996, inspirationally, or perhaps suspiciously, the year after Pocahontas’ release).[3] Writing about these Westerns in The Dream of Life J. Hoberman explains that,

'The most overtly ideological of revisionist Westerns addressed the subject of the Indian wars. In their open identification with Native Americans, such movies were the equivalent of marching for peace beneath a Viet Cong flag. Hollywood contra Hollywood: Cavalry Westerns were in production when My Lai was exposed, and the revelation of American atrocities only reinforced the argument that the slaughter of Native Americans was the essence of the white man’s war' (2003: 265).

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts

James Cameron’s eighth film, Avatar, was released in December 2009, the same year George W. Bush, the 43rd President of the United States, left office. Within weeks it became the highest grossing film of all time, one notch above Titanic (also a James Cameron film). The plot concerns Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic ex-marine in the 22nd century who joins an anthropological science team on the planet Pandora, and inhabits an avatar (a remote-controlled body) in the form of a member of the native population, the Na’vi, in order to gain military intelligence on them.

Although he performs his duty faithfully, he forms a bond with the Na’vi culture and becomes romantically involved with the daughter of the tribe’s leader, Neytiri (Zoe Saldana), which pits him in opposition to his superiors’ intention to destroy the Na’vi forest homeland in order to mine a valuable substance called Unobtainium.[1] This results in Sully leading the Na’vi in a revolt against the people of his birth nation and overthrowing them, eventually expelling them from Pandora. In the final frames of the film, Sully abandons his human body in a spiritual ceremony that permanently merges his consciousness with his physical Na’vi avatar, therefore completing his transformation into the indigenous culture and society.

In a thinly veiled allegorical parable, Avatar challenges blind submission to authority, both political and economic, while appearing to stand for the virtues of diversity and non-conformity, rebelling against authoritarianism and ethnocentrism. The story has been widely criticised for its clichéd and derivative nature.[2] It is not only similar to the Disney film Pocahontas (dir. Gabriel and Golberg, 1995), but has specific genre roots dating back even further to 1970’s revisionist Westerns (which incidentally is also the decade that Cameron first conceptualised his ideas for Avatar, although a film treatment would not be written until 1996, inspirationally, or perhaps suspiciously, the year after Pocahontas’ release).[3] Writing about these Westerns in The Dream of Life J. Hoberman explains that,

'The most overtly ideological of revisionist Westerns addressed the subject of the Indian wars. In their open identification with Native Americans, such movies were the equivalent of marching for peace beneath a Viet Cong flag. Hollywood contra Hollywood: Cavalry Westerns were in production when My Lai was exposed, and the revelation of American atrocities only reinforced the argument that the slaughter of Native Americans was the essence of the white man’s war' (2003: 265).

|

[1] According to Rebecca Keegan in The Futurist, ‘Unobtainium is a joke term engineers have used for decades to describe any needed material that is rare, costly, or difficult to obtain’ and goes on to quote Cameron saying ‘’it’s tea to the nineteenth-century British. It’s oil to twentieth-century America. It’s just another in a long list of substances that cause one group of people to…kick the shit out of another group’’ (2009: 253).

|

|

|

With Avatar then, Cameron seems to have recast the conventional science fiction genre to tell an allegory of the pernicious aspect of the recent political administration’s actions in Iraq in the way some 1970’s Westerns compared the slaughter of Native Americans with a contemporary American aggressive foreign policy. Native Indians may have been recast as the alien Na’vi (although retaining bows and arrows), but they are still a substitute for all foreign societies in conflict with the United States.[4]

Although this is not entirely original, the extremity of the film’s overt liberal and ecological attitude is rare in science fiction film, which more often submerges liberal agendas within conservative values, making their political statements indirectly. This is not to suggest that Avatar is completely free of this more traditional narrative, as in typical Cameron fashion, war scenes and portrayals of military equipment are often fetishised and even glorified throughout. As odd an juxtaposition as this seems, it may partly be due to the fact the genre actually tends to ‘flourish in conservative times, perhaps due to their escapist appeal to audiences appalled by contemporary reality’ (Booker, 2006: 14).

The emphasis here is on the rarity of an overt liberal agenda in Science Fiction film, not that liberal attitudes in the genre do not exist. In fact there is even a clear, justifiable argument in favour of claiming that the majority of science-fiction films lean to the left of the political scale, although it is not necessarily an inherent characteristic of the genre.

The emphasis here is on the rarity of an overt liberal agenda in Science Fiction film, not that liberal attitudes in the genre do not exist. In fact there is even a clear, justifiable argument in favour of claiming that the majority of science-fiction films lean to the left of the political scale, although it is not necessarily an inherent characteristic of the genre.

Planet of the Apes (dir. Franklin J. Schaffner, 1968) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1968) both serve as examples of Science Fiction films that can provide liberal readings, however in much subtler presentations than, for example, The Day the Earth Stood Still (dir. Robert Wise, 1951).

[2] A particularly scathing review can be found at ‘Avatar: Dances with clichés’, TheMillions.com,

http://www.themillions.com/2010/01/avatar-review-dances-with-cliches.html.

[3] There are also strong story comparisons with Star Wars (dir. George Lucas, 1977), Dune (dir. David Lynch, 1984) and Apocalypse Now (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979), particularly regarding the plot point of an outsider white messiah figure leading natives (discussed further in the book's section on race).

http://www.themillions.com/2010/01/avatar-review-dances-with-cliches.html.

[3] There are also strong story comparisons with Star Wars (dir. George Lucas, 1977), Dune (dir. David Lynch, 1984) and Apocalypse Now (dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979), particularly regarding the plot point of an outsider white messiah figure leading natives (discussed further in the book's section on race).

RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II ...IN SPACE!

Yet these films almost always maintain the overall ideology that the American nation is ‘the good guy’.[5] Hence movies such as Predator (dir. John McTiernan, 1987) and Stargate (dir. Roland Emmerich, 1994) which although at brief moments find time to sympathise with the alien foe, always ultimately culminates in our heroes blasting them away in favour of an ‘us versus them’ policy, despite any moral objections that may arise (although Predator is more about self-defence against an attacking alien, its setting in a central American jungle still allows for a reading that suggest it is an American invasion of foreign territory). Starship Troopers (dir. Paul Verhoeven, 1997) also portrays an Earth (American) victory over an alien foe in a war that had been begun by humans, however the film’s satirical subtext redeems it to an extent.

Yet these films almost always maintain the overall ideology that the American nation is ‘the good guy’.[5] Hence movies such as Predator (dir. John McTiernan, 1987) and Stargate (dir. Roland Emmerich, 1994) which although at brief moments find time to sympathise with the alien foe, always ultimately culminates in our heroes blasting them away in favour of an ‘us versus them’ policy, despite any moral objections that may arise (although Predator is more about self-defence against an attacking alien, its setting in a central American jungle still allows for a reading that suggest it is an American invasion of foreign territory). Starship Troopers (dir. Paul Verhoeven, 1997) also portrays an Earth (American) victory over an alien foe in a war that had been begun by humans, however the film’s satirical subtext redeems it to an extent.

[4] Oddly enough Avatar shares a strong similarity to a Western film dating as far back as the early 1950s. Broken Arrow (dir. Delmer Daves, 1950) is the story of Tom Jeffords (James Stewart), a white man who befriends an Apache Indian, marries an Indian girl, and becomes a peacemaker between the Apaches and whites. He is considered a traitor by his own people, and a nearby town forms a mob that attacks the Indian camp. Upon its release the film was considered unpatriotic by more conservative viewers, much as Avatar is now.

|

|

Even science fiction films famous for their quite liberal attitudes, such as the Star Trek film franchise (1979 – present) eventually abandon diplomacy for a gung-ho attitude toward each story’s climax, reasserting America’s right due to its military might. And for all its liberal rhetoric, Star Trek is virtually United States propaganda in its representation of American gunship diplomacy. So as a rule, current foreign policy in science fiction film, despite any critical moral objections along the way, will most often become Rambo: First Blood Part II in space.[6]

John Belton explains in American Cinema / American Culture that the primary reason for this portrayal of foreign policy is that,

'Wars are waged on two fronts – on the battlefield and on the screen. Hollywood’s job has been to make sure not that we always win but that we are always right – that our victories are informed by an inherent pacifism and distaste for war that redeems us from the sins of our conscienceless enemies and that our single defeat (in Vietnam) is the product not of our consciouslessness [sic] but of our heightened consciousness, which sets us against ourselves and provides the basis for the recasting of our defeat as a victory in Hollywood’s various epilogues to the war' (1994: 182).

John Belton explains in American Cinema / American Culture that the primary reason for this portrayal of foreign policy is that,

'Wars are waged on two fronts – on the battlefield and on the screen. Hollywood’s job has been to make sure not that we always win but that we are always right – that our victories are informed by an inherent pacifism and distaste for war that redeems us from the sins of our conscienceless enemies and that our single defeat (in Vietnam) is the product not of our consciouslessness [sic] but of our heightened consciousness, which sets us against ourselves and provides the basis for the recasting of our defeat as a victory in Hollywood’s various epilogues to the war' (1994: 182).

|

[5] Even a Science Fiction film as liberal as Logan’s Run (dir. Michael Anderson, 1976) which espouses a strict anti-authoritarian theme taking place in a 23rd century domed colony, ultimately portrays America as its saviour, rather than oppressor as its protagonists (played by Michael York and Jenny Agutter) escape to ruined American landmarks. Science fiction film has rarely gone as far as the Vietnam War genre in overtly suggesting that America is the enemy. Reversely, very few in the Vietnam War genre do not in fact, The Green Berets (dir. Kellogg and Wayne, 1968) serving as a rare example.

|

[6] A film famous for its portrayal of a victorious return to the Vietnam War through excessive American aggression, it is particularly ironic that Rambo: First Blood Part II can be used as an example of the ultimate antithesis of Avatar as it was also penned by James Cameron, although later drastically altered by Sylvester Stallone.

|

|

Not a war film, but one of the rare examples of a an overtly liberal and ecological science fiction film that can be politically aligned with Avatar is Silent Running (dir. Douglas Trumbull, 1972), in which an astronaut forest ranger disobeys his superiors in order to preserve an orbital woodland, turning against and eventually murdering his fellow crew members to do so.[7] While the basic plot shares similarities with Avatar in that both heroes are trying to save a forest and must kill some of their peers in order to accomplish it, the films fork away from one another in their endings.

|

Avatar has a victorious Jake Sully save the forest from destruction and exiling his former corporate superiors, while Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern) of Silent Running dies for his ‘crimes’ and his forest floats out into deep space, its maintenance by a single small robot with a battered watering can a bittersweet epilogue of the long-term futility of his resistance.

Even compared to Cameron’s previous work, such an overtly politically liberal kindred spirit is rare. For example, Aliens features a similar storyline in that it is about a group of humans who attempt to colonise an alien world (albeit not native to the eponymous aliens in the title) and after opposition, escape it and detonate a nuclear bomb. While still critical of foreign policy on one level, the more overt message of this film would appear to be in direct contrast to that of Avatar, as it suggests an all-or-nothing policy, as opposed to the preference of non-interference told on Pandora. On a more liberal note, it does criticise corporatism and its use of military, although its plot of fighting aliens in space with excessive military hardware is also the embodiment of Reagan’s Star Wars programme. With the exception of a strong anti-nuclear stance, The Terminator films also follow suit.

|

|

Due to his films being post-modern (disallowing the use of sharp classifications), individually they ‘lend themselves easily to readings both progressive and conservative’, theorises Alexandra Keller in The Routledge Guidebook to James Cameron, but concludes that if viewed as a group ‘his conservative ideology comes to the fore’ (2006: 7).

AN END TO WAR?

His one other more liberal exception before Avatar is the special edition of The Abyss. In it, extra-terrestrials disparaged with humanity and an escalating Cold War nihilistically create world-wide tsunamis to ‘solve’ the problem, but cease to employ them after the film’s protagonist Virgil ‘Bud’ Brigman (Ed Harris) shows them that human beings are also capable of compassion and love. Like Avatar then, it is human governments and military that are to blame for a perception of humanity as compassionless, specifically represented by Navy Seal Lt. Hiram Coffey (Michael Bien), a prototype of Avatar villain Col. Quaritch (Stephen Lang), which takes us to the brink of extinction.

AN END TO WAR?

His one other more liberal exception before Avatar is the special edition of The Abyss. In it, extra-terrestrials disparaged with humanity and an escalating Cold War nihilistically create world-wide tsunamis to ‘solve’ the problem, but cease to employ them after the film’s protagonist Virgil ‘Bud’ Brigman (Ed Harris) shows them that human beings are also capable of compassion and love. Like Avatar then, it is human governments and military that are to blame for a perception of humanity as compassionless, specifically represented by Navy Seal Lt. Hiram Coffey (Michael Bien), a prototype of Avatar villain Col. Quaritch (Stephen Lang), which takes us to the brink of extinction.

|

Both featuring a crazed military man, a protagonist who must slowly win the heart of a strong-willed woman, and the themes of war and economy, interestingly The Abyss was released the year President George Bush Senior entered office (January 20th 1989), and Avatar just after his son, George Bush Junior, left (January 20th 2009). This is not to suggest that Cameron has particular grievances with the Bush family, but reflects the perceived oncoming eras of peace that were imminent during both time periods. During The Abyss era virulent anti-Soviet President Ronald Reagan had just left office while glasnost and perestroika were bringing the Cold War to an end.

|

[7] Silent Running is a rare, but not singular example. Other films include, but are not limited to, Soylent Green (dir. Richard Fleischer, 1973), and Wall-E (dir. Andrew Stanton, 2008), although their narrative structures do not mirror Avatar quite as closely as Silent Running does.

|

This theme of international cooperation emerged from the Cameron film, as well as many others of the era that followed. For example, by 1990 relations were so good that Hollywood could feature an heroic Soviet submarine captain (Capt. Marko Ramius played by Sean Connery) in The Hunt for Red October (dir. John Mctiernan) while the Rambo films, which had proved very popular only a few years earlier became distastefully unwelcome, Rambo III (dir. Peter MacDonald, 1988) flopping at the box-office. Avatar was also made in an era on the cusp of perceived peace, as after more than half a decade of war President Obama’s election brought with it the promise of the return of troops from Iraq and Afghanistan.

In summary then, this is what we now know of Avatar...

The plot draws parallels with other films critical of foreign policy, specifically following the template of revisionist Westerns. It is more overtly liberal than most in the science-fiction genre, but comfortably tows the line with many in the Vietnam War genre. The film has a duel personality with conservatism, which appears to be a default position in the work of Cameron, but makes a conscious effort at liberalism, perhaps as a reflection of the attitude of its American audience, (on the one hand concerned about cost and standards of living due to oil prices, but on the other not wanting to be responsible for the immorality of war).

This overt liberal political position does not sit well within the Cameron cannon, or indeed entirely within Avatar itself. Although not completely alien, having been expressed before to much lesser degrees, we conclude that his latest film is arguably overall politically left of centre. Considered in light of domestic and international politics then, Avatar reflects the transitional era from that of the recent Bush administration into that of Obama, namely Sully’s accomplishments in the film culminating in actions that have also been promised by the current President (sending troops home from foreign territory). In order to expand on these ideas, further investigation into the film’s relationship with the War genre and the Bush administration would enlighten us as to its relevance to a contemporary audience...

The plot draws parallels with other films critical of foreign policy, specifically following the template of revisionist Westerns. It is more overtly liberal than most in the science-fiction genre, but comfortably tows the line with many in the Vietnam War genre. The film has a duel personality with conservatism, which appears to be a default position in the work of Cameron, but makes a conscious effort at liberalism, perhaps as a reflection of the attitude of its American audience, (on the one hand concerned about cost and standards of living due to oil prices, but on the other not wanting to be responsible for the immorality of war).

This overt liberal political position does not sit well within the Cameron cannon, or indeed entirely within Avatar itself. Although not completely alien, having been expressed before to much lesser degrees, we conclude that his latest film is arguably overall politically left of centre. Considered in light of domestic and international politics then, Avatar reflects the transitional era from that of the recent Bush administration into that of Obama, namely Sully’s accomplishments in the film culminating in actions that have also been promised by the current President (sending troops home from foreign territory). In order to expand on these ideas, further investigation into the film’s relationship with the War genre and the Bush administration would enlighten us as to its relevance to a contemporary audience...

|

This article is an extract from new book 'The Film Reader's Guide To James Cameron's AVATAR - Understanding how the sci-fi epic reflects its historical and cultural context' by Bryn V. Young-Roberts. Available from Amazon and various other stockists.

|

Before You Go...

If you've enjoyed exploring what James Cameron's Avatar says about 21st Century America then our next article might also be of interest:

Watchmen: Post-Modernism, Gender And Sexuality In America

Also Worth Checking Out

If you've enjoyed exploring what James Cameron's Avatar says about 21st Century America then our next article might also be of interest:

Watchmen: Post-Modernism, Gender And Sexuality In America

Also Worth Checking Out

|

|