Watchmen: Post-Modernism, Gender and Sexuality - How Zach Snyder's Film Portrays Superheroes and Reflects American History

|

|

WATCHMEN (2009)

'HUMAN BEAN JUICE'[1]

'HUMAN BEAN JUICE'[1]

|

POST-MODERNISM, GENDER AND SEXUALITY: HOW WATCHMEN PORTRAYS SUPERHEROES AND REFLECTS AMERICAN HISTORY

By Bryn V. Young-Roberts ‘I’M JUST A PUPPET WHO CAN SEE THE STRINGS’[2] HOW TO WATCH WATCHMEN

Human beings are largely a product of their culture, and so as an extension of human thought and expression popular culture films should therefore be a reflection of the society that created them. This is due to cultural influences upon the filmmakers to code their movies with certain messages (intentionally or unintentionally), but also the audience deriving meaning from them as culturally-influenced spectators. However in the postmodern era meaning is becoming an increasingly fluidic concept to many filmmakers and spectators alike.

|

If we were to stick too rigidly to postmodern concepts and say that there is no meaning in anything however, then this would be a very short article. Instead, examinations of postmodern elements are complemented by cultural studies, employed to explore possible meanings and dimensions ironically impenetrable by the radical grand narrative of postmodernism that states there is no universal truth.

Postmodernism has no clear definition that has not been contested or widely accepted. The Idea of the Postmodern (Bertens, 1995) successfully discusses its main factors, and so will act as the basis for understanding postmodern theory in this work. Bertens surmises that the basic ingredients, most of which stem from modernism, are a lack of distinction between high and low art (popular culture), multiple and discontinuous narratives (including mini-narratives), fragmented forms, blurring distinctions of genre, a self-conscious reflexivity, pastiche, parody, bricolage and irony, an acceptance of the world as meaningless, a criticising of grand narratives and a belief that knowledge is functional and that the world is the domain of the consumer market (evolved in a world of electronics and nuclear power).

Postmodernism has no clear definition that has not been contested or widely accepted. The Idea of the Postmodern (Bertens, 1995) successfully discusses its main factors, and so will act as the basis for understanding postmodern theory in this work. Bertens surmises that the basic ingredients, most of which stem from modernism, are a lack of distinction between high and low art (popular culture), multiple and discontinuous narratives (including mini-narratives), fragmented forms, blurring distinctions of genre, a self-conscious reflexivity, pastiche, parody, bricolage and irony, an acceptance of the world as meaningless, a criticising of grand narratives and a belief that knowledge is functional and that the world is the domain of the consumer market (evolved in a world of electronics and nuclear power).

|

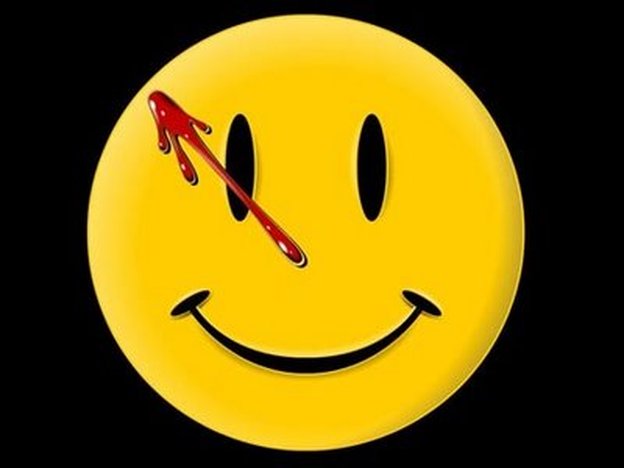

[1] Rorschach’s description of the blood of one of his colleagues on a smiley face badge.

The smiley face with blood on it embodies the postmodern attitude of the film, as it is simultaneously fun and ironic, bearing the grin of the badge, yet harbouring the remains of a murder victim. Additionally, it is also a link to the early 1970s, considered by some to be a transitional time of the loss of innocence in America and therefore disrupting any held notions of history and continuity the audience might have. [2] Dr Manhattan on his perception of time. |

Unlike modernism however, it is important to point out that postmodernism delivers pastiche, parody, bricolage and irony with a sense of playfulness, while celebrating fragmented forms and incoherence rather than pressing on their tragic qualities. It does not necessarily blame institutions for their grand narratives, but rather accepts that they are at the mercy of the lack of a permanent, stable reality and are trying to mask contradictions and instabilities, which leave them vulnerable for criticism. Mini-narratives are therefore preferred as they highlight the situational, temporary, contingent, and provisional while making no claim on universal truth. Never outlining the key elements of postmodernism in a simple format, Bertens describes them thus:

‘Postmodernism is the move away from narrative, from representation… [it] is the turn towards self-reflexiveness in the so-called metafiction [sic] (1995, p4).[3]

This postmodernism interrogates the power that is inherent in the discourses that surround us – and that is continually reproduced by them – and interrogates the institutions that support these discourses and are, in turn, supported by them. It attempts to expose the politics that are at work in representations and to undo institutionalized hierarchies, and it works against the hegemony of any single discursive system (1995, 8).

[It is the] ever-increasing commodification of both the public and the private (1995, p10).

Inevitably, this re-evaluation of culture has led to an interest in the origins and history of specific representations…postmodernism has for instance led to a spectacular upgrading of cultural studies (1995, p11)’.

Cultural studies are the methods employed to explore these origins. Not a lone critical theory, cultural studies is a term unifying a collection of methods that examine texts within broader cultural, social, industrial and political networks of power. It attempts to understand how different groups read texts due to their historical context and situation of reception, despite a dominant ideology. Drawing on politics, sociology and semiotics, it accepts spectatorship as an active part of textual decoding, and interprets both contemporary and classical texts with regard to sexual, feminist and racial perspectives. The main components relevant to this article are queer theory, historical reception and feminist thought on gender. While the latter method is known widely enough not to get into detail here (although points will be brought up when discussing it), and historical reception is largely self-explanatory, queer theory is less well known, but becoming increasingly popular.

Mostly based on work pioneered in Gender Trouble (Butler, 1990), queer theory is the acceptance that ideas of identity are not fixed, and challenges that such notions determine who we are. Heidi Kaye and I.Q. Hunter define it in Alien Identities:

‘…We define ourselves through defining the other: we are what we are not… we attempt to reconstruct an ‘other’ from which to distinguish ourselves in a binary opposition. The notion of identity tends to be exclusive rather than inclusive, creating hierarchies and prejudice on the basis of class, race, gender, nationality and sexual orientation (1999, p3)’.

According to this theory, it is not possible to generalise people in any serious way of understanding them, such as applying a shared characteristic, as there are too many elements involved in the make-up of each individual. This is a theory that fits in well with post-modernist thought, as it examines the cracks in an assumed grand narrative.

‘Postmodernism is the move away from narrative, from representation… [it] is the turn towards self-reflexiveness in the so-called metafiction [sic] (1995, p4).[3]

This postmodernism interrogates the power that is inherent in the discourses that surround us – and that is continually reproduced by them – and interrogates the institutions that support these discourses and are, in turn, supported by them. It attempts to expose the politics that are at work in representations and to undo institutionalized hierarchies, and it works against the hegemony of any single discursive system (1995, 8).

[It is the] ever-increasing commodification of both the public and the private (1995, p10).

Inevitably, this re-evaluation of culture has led to an interest in the origins and history of specific representations…postmodernism has for instance led to a spectacular upgrading of cultural studies (1995, p11)’.

Cultural studies are the methods employed to explore these origins. Not a lone critical theory, cultural studies is a term unifying a collection of methods that examine texts within broader cultural, social, industrial and political networks of power. It attempts to understand how different groups read texts due to their historical context and situation of reception, despite a dominant ideology. Drawing on politics, sociology and semiotics, it accepts spectatorship as an active part of textual decoding, and interprets both contemporary and classical texts with regard to sexual, feminist and racial perspectives. The main components relevant to this article are queer theory, historical reception and feminist thought on gender. While the latter method is known widely enough not to get into detail here (although points will be brought up when discussing it), and historical reception is largely self-explanatory, queer theory is less well known, but becoming increasingly popular.

Mostly based on work pioneered in Gender Trouble (Butler, 1990), queer theory is the acceptance that ideas of identity are not fixed, and challenges that such notions determine who we are. Heidi Kaye and I.Q. Hunter define it in Alien Identities:

‘…We define ourselves through defining the other: we are what we are not… we attempt to reconstruct an ‘other’ from which to distinguish ourselves in a binary opposition. The notion of identity tends to be exclusive rather than inclusive, creating hierarchies and prejudice on the basis of class, race, gender, nationality and sexual orientation (1999, p3)’.

According to this theory, it is not possible to generalise people in any serious way of understanding them, such as applying a shared characteristic, as there are too many elements involved in the make-up of each individual. This is a theory that fits in well with post-modernist thought, as it examines the cracks in an assumed grand narrative.

|

|

|

[4] Nite Owl II discusses how he prefers to view the world via two-tone goggles, as it becomes easier to interpret.

|

‘WHENEVER I LOOK THROUGH THOSE GOGGLES, EVERYTHING IS CLEAR AS DAY’[4]

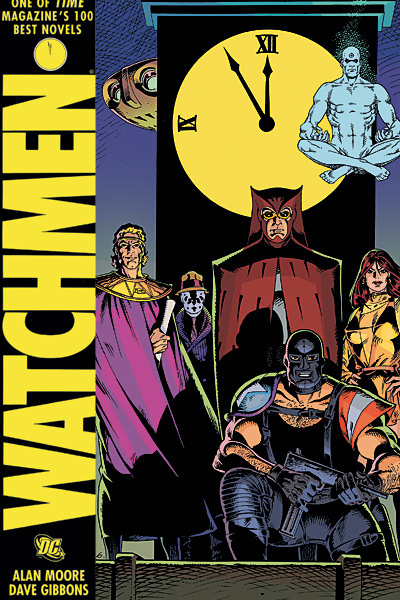

WATCHING THE WATCHMEN Watchmen (2009) is a film based on twelve-issue comics by graphic novel auteurs Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. The film version follows the plot and themes of the comic book relatively closely, or at least more faithfully than most superhero screen adaptations. There are some differences, but they are not of particular importance to this article, which is not concerned with comic-to-film transfusion. Differences between the graphic novel and the movie will be highlighted occasionally, though only if it is relevant to a point being made about the film.

The story is set in 1985 New York, in an alternative universe. The main differences to the world of our 1985 are a President Nixon who has amended the US Constitution to remain in office for 5 consecutive terms, a history of costumed crime-fighters existing in the real world rather than in comics (which are populated by pirate stories in their place), minor technological differences which are never fully explained (but appear to include genetic engineering), and an American victory in the Vietnam war. Cold war tensions seem to be intact, although the impression is given that they are escalating rather than decreasing (via a media obsessed with the doomsday clock), in an era that in our world saw tensions ease with the developments of glasnost. This is due to the existence of Dr Manhattan (Billy Crudup), a being with genuine omnipotence who has upset the balance of terror by aligning himself with America. He is also the only superhero in the film with any real super-powers. The narrative begins with the murder of Edward Blake (Jeffrey Dean Morgan), a former costumed vigilante known as the Comedian, who has uncovered a plot by fellow retired superhero Adrian Veidt (Mathew Goode) to unite world superpowers through nefarious means. |

Masked vigilante Rorschach (Jackie Earle Haley) investigates the death, and along the way involves Dan Dreiberg (Patrick Wilson) and Laurie Jupiter (Malin Akerman), who themselves are former costumed heroes Nite Owl II and Silk Spectre II, respectively. Over the course of the film very few plot motions occur, the detective aspects of the investigation only accounting for a few beats (Rorschach questioning Edgar Jacobi (Matt Frewer), and Nite Owl II discovering a file on Veidt’s computer, being the most significant developments).

However as it unfolds the audience are exposed to revealing information about the characters. We discover Comedian to be a cynic, attempted rapist, and extremist right-wing patriot who worked for the Nixon regime. The ‘saviour’ of America, Dr Manhattan is becoming increasingly apathetic to human existence. Drieberg has penis trouble relating to his alter ego. Rorschach is insane and too judgmental to fit into the society he wants to protect, while Veidt (former superhero name Ozymandias) has blurred the line of moral ambiguity necessary to be a superhero so far in his attempt to save the world, that he has become the unethical villain of the story.

Pirouetting from superhero genre films of the past, it shows a world where the public hates caped crusaders, and delivers an ending that sees the ‘villain’ achieving his goals. It even kills off the plot’s chief advancer, Rorschach. Framing Dr Manhattan for the crime, Veidt destroys several cities all over the world, which unites nations against the more powerful nemesis. Further to this, the ‘heroic’ action taken by Dr Manhattan is to take the blame, murder Rorschach in order to secure it, and flee to another galaxy. The only happy ending is that Drieberg’s penis trouble has been cured (or rather, indulged by his fetish) and that Rorschach’s journal, found by an assistant newspaper editor, may enlighten the world to Veidt and Dr Manhattan’s deceit (which would be a hollow victory as it would end world peace).

However as it unfolds the audience are exposed to revealing information about the characters. We discover Comedian to be a cynic, attempted rapist, and extremist right-wing patriot who worked for the Nixon regime. The ‘saviour’ of America, Dr Manhattan is becoming increasingly apathetic to human existence. Drieberg has penis trouble relating to his alter ego. Rorschach is insane and too judgmental to fit into the society he wants to protect, while Veidt (former superhero name Ozymandias) has blurred the line of moral ambiguity necessary to be a superhero so far in his attempt to save the world, that he has become the unethical villain of the story.

Pirouetting from superhero genre films of the past, it shows a world where the public hates caped crusaders, and delivers an ending that sees the ‘villain’ achieving his goals. It even kills off the plot’s chief advancer, Rorschach. Framing Dr Manhattan for the crime, Veidt destroys several cities all over the world, which unites nations against the more powerful nemesis. Further to this, the ‘heroic’ action taken by Dr Manhattan is to take the blame, murder Rorschach in order to secure it, and flee to another galaxy. The only happy ending is that Drieberg’s penis trouble has been cured (or rather, indulged by his fetish) and that Rorschach’s journal, found by an assistant newspaper editor, may enlighten the world to Veidt and Dr Manhattan’s deceit (which would be a hollow victory as it would end world peace).

|

Not only does the ending reflect a postmodern outlook by blurring the tradition of the genre[5] for the hero to save the day and kill the villain, but also the moral ambiguity and ethical dilemma of murdering Rorschach leaves viewers with a fragmented conclusion, and no universal truth on the issue. Instead, the audience is invited to determine their own moral conclusion, with a playful nod from the prospect of Rorschach’s journal encouraging them to do so quickly.

There appears to be nothing postmodern about the plot, which essentially consists of a murder, a brief investigation revealing it was a colleague, and then an attempt to thwart him.[6] Not to be confused with an Agatha Christie novel though, the thin plot only serves as a skeletal structure for a collection of shorter narratives. By delving into these mini-narratives, the film subscribes to postmodern ideas of embracing the temporal and situational over a grand narrative, which can offer no universal truth on the ethical issues raised in the film. |

[5] Further to this blurring of the genre, although Watchmen meets the criteria of being defined as a superhero genre film, the narrative, sub-plots and themes of the film focus more on the lives of the heroes outside of costume than it does in, begging questions about those very definitions.

[6] A lack of attention to the importance of realism, characterization, or plot is a common trait of postmodernism. |

‘THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’[7]

THE TIME OF WATCHMEN

The Watchmen comics were created in late 1986, and ran until late 1987. This is at a time when Chernobyl increased fear of nuclear power, New Zealand refused port entry to US nuclear warships, and America was dropping bombs on Libya.

While the constant news headlines about nuclear topics might account for an on-going sense of apocalyptic dread (and the theme of the Doomsday clock), the build-up of military might and attacks under Reagan could be responsible for the sense of increasing paranoia regarding authorities. Also largely influential on paranoia must have been the fact that the comics were developed in Great Britain, which saw the post-industrial revolution leading to a lack of job security and increased police brutality under the Thatcher Conservative government.

THE TIME OF WATCHMEN

The Watchmen comics were created in late 1986, and ran until late 1987. This is at a time when Chernobyl increased fear of nuclear power, New Zealand refused port entry to US nuclear warships, and America was dropping bombs on Libya.

While the constant news headlines about nuclear topics might account for an on-going sense of apocalyptic dread (and the theme of the Doomsday clock), the build-up of military might and attacks under Reagan could be responsible for the sense of increasing paranoia regarding authorities. Also largely influential on paranoia must have been the fact that the comics were developed in Great Britain, which saw the post-industrial revolution leading to a lack of job security and increased police brutality under the Thatcher Conservative government.

|

[7] Bob Dylan, Watchmen soundtrack, opening titles montage sequence. The use of this music artist implies a tone of social unrest for which he is famous. On a separate note, music in the film ranges from pop (99 Luftballons) to classical (Requiem aeternam), showing a lack of distinction between high and low art.

[8] More Information about Goetz found at http://www.heroism.org/class/1980/goetz.htm |

The vigilante theme and the moral ambiguity in the comic is what appears to have the most resonance with the times it was created, particularly with its New York setting. The trial of Bernhard Goetz[8] sparked debate about vigilantism after he shot and seriously wounded four muggers in a Manhattan subway just before Christmas 1984 (incidentally, in the comic Rorschach is cited as having killed four people in his career as a vigilante). Simultaneously vilified and exalted by a divided media, Goetz’s actions were viewed as the product of a frustration, shared by many, at the high crime rates in the city. Just as in Watchmen, there were no conclusive answers to any of the debates about the moral right of his actions. Even at trial, Goetz could only be found guilty of illegal firearms possession, despite the accusations of his intent to bear arms and deliberately seek a situation in which to defend himself.

|

|

Certain elements of the graphic novel have found a reinvigoration in the 21st century. Police brutality still occurs in the 21st century, possibly worse in America now than ever,[9] making the film’s theme of questioning the actions of justice enforcers as relevant as in the 1980’s, if not more so.

The media hysteria over paedophilia makes the scene setting up the rigidity of Rorschach’s convictions more poignant than ever. While in the comic he punishes the murderer of a little girl by setting him on fire (which the reader does not see), but he also gives him an opportunity to escape (albeit a token gesture to very flimsily satisfy any notions of fair justice). In the film version not only is this token gesture missing, but in a fashion that would make a slasher movie blush, he repeatedly hacks into the man’s head with a meat cleaver (all clearly seen on camera and continuing to do so even after the man is obviously dead). This seems to be an updated, hard-line, and passion-filled attitude toward an issue that has become a media obsession, due in no small part to the increase in paedophilia[10] since the dawn of the internet.[11] Much of the themes and issues carried forward to our time are directly related to postmodern ideas of repetition and simulacrum, as Gary Aylesworth explains: ‘Instead of calling for experimentation with counter-strategies and functional structures… the heterogeneity and diversity in our experience of the world as a hermeneutical problem [is] to be solved by developing a sense continuity between the present and the past. This continuity is to be a unity of meaning rather than the repetition of a functional structure, and the meaning is ontological (Stanford Encyclopaedia, 2005)’. [12] Newspaper headlines and TV news reports about a Soviet invasion of Afghanistan litter the film, but take on an ironic twist in 2009 that was not present in the 1980’s, as the more recent invasion was conducted by the West. This highlights the nature of human beings, irrespective of ideology, and the inevitability of historical patterns due to it. Of even more poignancy is the Nixon regime. Having silenced Woodward and Bernstein (implied to have been conducted by the Comedian), there appears to have been a death of intelligent liberal journalism in the film. As the Keene act prevents the operations of masked crusaders, parallels are drawn to the recent Bush administration and the curtailing of civil liberties.[13] Both Nixon and Bush seem intent on limiting the involvement of individuals, or groups of activists, in governmental matters, although doing so creates an ethical conundrum for society as it means there is no safeguard from an overzealous political authority. |

[9] More information about police brutality at http://www.inthesetimes.com/

article/4268/will_holder_hold_cops_accountable/ [10] More information about the increase in paedophilia at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/3254382.stm [11] Of course the Internet is a device of the postmodern era, as Gary Aylesworth explains ‘the computer age has transformed knowledge into information, that is, coded messages within a system of transmission and communication’, emphasising the value of knowledge as perceived through language. However mainstream computer technology in Watchmen seems just as limited as in the 1985 of our universe, and so makes little impact on a postmodern understanding of this aspect of the film. Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (2005) Available at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/postmodernism/#7 [12] Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (2005) Available at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/postmodernism/#7 [Accessed December 2009]. [13] Information about the Bush administration retreating civil liberties found at http://www.slate.com/id/2156397/ |

As a blockbuster of 2009 however, Watchmen the movie is carrying additional cultural baggage. Like the comic, it features a disastrous attack in New York. Unlike the comic, the film has to deal with an audience that has already witnessed this in real life. Throughout the film the World Trade Centre makes several appearances in a misty background, but is never directly referred to, as though it were a memory from the future. In one scene that discusses a nuclear apocalypse, the twin towers can be seen through a window with a blimp resembling an aircraft carrier bomb moving closer to them, as though it were a nod to future events. In this sense the film is not only translating a feeling of doom to a post-cold war audience, but reinforces the postmodern sense of repetition in time.

Another scene sees the towers watching over a military funeral, the American flag on the coffin now an all too familiar sight, as the audience is invited to draw a connection between the two. The man being buried is the Comedian, who fought in a victorious Vietnam War. Interpreted with the earlier blimp scene that suggests the events of 9/11 are still to occur, it draws parallels between the recent Afghanistan and Iraq wars by highlighting the human cost, satirising that American confidence will inevitably be taken aback sooner or later in a futile fight against human nature in a linear time.

When they are seen later on, they not only serve as a reminder of history by standing behind a devastated New York that resembles ground zero (a simulacrum metanarrative that alludes to events beyond the framework of the film characters’ narrative), but also act as a beacon of hope. By having survived the destruction of New York City they appear at a time in the film immediately after Dr Manhattan has come to think of time as alterable and so their intact presence simultaneously serves as a current understanding of disaster and hope for the future.[14]

Unfortunately, Rorschach’s journal later implies that Dr Manhattan was wrong, and human nature is destined to lead to their destruction once more. Yet in typical postmodern style, it is delivered with a playful tone that asks the audience to decide on the level of optimism or pessimism necessary. After all, none of it really means anything. Does it?

‘ALL IT TOOK WAS A NICE PAIR OF LEGS’[15]

THE WATCHING MEN

A surprising element of the graphic novel that has been kept in the film is the sexist role of women regularly seen in the world of adolescent male comics. All the women in Watchmen, with the exception of female newsreaders and guests on current affairs programmes, have one thing in common. They are victims of men within some sort of sexual context. The girl murdered by the paedophile was obviously at the mercy of a more powerful male, a pregnant Vietnamese woman is shot dead by her lover the Comedian, and prostitutes crowd the streets as both victims and criminals of the male sexual appetite.

The only woman who doesn’t initially appear to be oppressed by male sexual domination is a protestor who tells Comedian (who is holding a large gun), to ‘Fuck Off!’ in a particularly aggressive manner. Essentially she is grasping the concept of sexual dominance, in the face of a large symbolic phallus, and throwing it back at the most sexually aggressive male in the film.

When they are seen later on, they not only serve as a reminder of history by standing behind a devastated New York that resembles ground zero (a simulacrum metanarrative that alludes to events beyond the framework of the film characters’ narrative), but also act as a beacon of hope. By having survived the destruction of New York City they appear at a time in the film immediately after Dr Manhattan has come to think of time as alterable and so their intact presence simultaneously serves as a current understanding of disaster and hope for the future.[14]

Unfortunately, Rorschach’s journal later implies that Dr Manhattan was wrong, and human nature is destined to lead to their destruction once more. Yet in typical postmodern style, it is delivered with a playful tone that asks the audience to decide on the level of optimism or pessimism necessary. After all, none of it really means anything. Does it?

‘ALL IT TOOK WAS A NICE PAIR OF LEGS’[15]

THE WATCHING MEN

A surprising element of the graphic novel that has been kept in the film is the sexist role of women regularly seen in the world of adolescent male comics. All the women in Watchmen, with the exception of female newsreaders and guests on current affairs programmes, have one thing in common. They are victims of men within some sort of sexual context. The girl murdered by the paedophile was obviously at the mercy of a more powerful male, a pregnant Vietnamese woman is shot dead by her lover the Comedian, and prostitutes crowd the streets as both victims and criminals of the male sexual appetite.

The only woman who doesn’t initially appear to be oppressed by male sexual domination is a protestor who tells Comedian (who is holding a large gun), to ‘Fuck Off!’ in a particularly aggressive manner. Essentially she is grasping the concept of sexual dominance, in the face of a large symbolic phallus, and throwing it back at the most sexually aggressive male in the film.

|

[14] The presence of the towers in the background may also be trying to suggest something else. A mistrust of history can also be considered a facet of postmodernism.

The plot of the film (attacking New York with a fake enemy) could be interpreted as a satire aimed at the Bush administration from the perspective of popular conspiracy theories regarding the destruction of the twin towers. More information is available at http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2006/sep/ 05/internationaleducationnews.highereducation [15] Rorschach’s judgmental comment on Nite Owl II’s motivation for returning to the Superhero lifestyle. [16] Emphasis in original. |

However it is ultimately a weak gesture, as she can only do so verbally, without any real power, emphasising the oppression further. Even A-sexual Rorschach doesn’t give women an easy time, describing them as ‘whores’ for sleeping with men (his mother was also a prostitute).

The female superheroes do not escape the poor reception either. In The Psychology of Superheroes Johnson, Lurye and Freeman describe gender role identification as thus: ‘The very nomenclature of superheroes suggests that the gender of supers is a critical aspect of their identity. Supers’ names, for example, frequently highlight not only an exceptional talent, but also their sex. This is true for both female (e.g. wonder-woman, super-girl, She-ra, Powerpuff Girls, Vampirella, Invisible Girl, and Elasti-girl) and male (Superman, He-man, Spider-man, Mr Fantastic, Mr Incredible) superheroes… In addition to possessing super-human powers, superheroes possess a super-human gender as well. Indeed, even the Supers whose names do not connote their gender (e.g. Storm from X-Men) remain highly gender stereotyped in form and function… certain gender cues are extremetized to magnify the differences between men and women (e.g. body size and body shape), while others are amplified to accentuate valued gendered traits (2008, p230)’.[16] |

|

|

Laurie’s mother, Sally Jupiter (Carla Gugino) fits this bill precisely. In the scenes of her set during her days as a superhero (Silk Spectre – note the sexual connotations of silk[17]) she demonstrates an indulgence in her sexual allure (her exaggerated gender role), while in the scenes of her as an old woman, with alcoholic refreshment in hand, she mourns the loss of her power to attract men. Incidentally, her daughter Laurie first becomes involved with Dr Manhattan when he leaves his partner because she has grown old[18]. This reinforces ideas that female roles in comics are mostly for male scopophilia. As Mary Evans explains in Introducing Contemporary Feminist Thought,

‘…Women’s appearance, indeed our very identity, is constructed for a male gaze and may be far from expressing any real independence or autonomy. Again the argument is complicated by a perception - derived from Western feminism – that the appearance of women is often closely related to the power and status of their male partners’ (1997, p125).

‘…Women’s appearance, indeed our very identity, is constructed for a male gaze and may be far from expressing any real independence or autonomy. Again the argument is complicated by a perception - derived from Western feminism – that the appearance of women is often closely related to the power and status of their male partners’ (1997, p125).

|

[17] Also note the Spectre part of her name in relation to her life as an object for men. Citing Marx, Gary Aylesworth points out in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy website that ‘We have an analysis of the fetishism of commodities (Marx 1983, 444-461) where objects lose the solidity of their use value and become spectral figures under the aspect of exchange value. Their ghostly nature results from their absorption into a network of social relations, where their values fluctuate independently of their corporeal being’.

|

[18] On a different subject matter this also reinforces a sense of repetition through time due to human nature, particularly as Dr Manhattan is a character somewhat outside the confines of time and yet he is still attracted to the latest young woman and wants to discard of his older one. This is a point also suggested in the film by the inheritance of superhero names from one generation to the next (e.g. Nite Owl and Nite Owl II, Silk Spectre and Silk Spectre II), especially as it shows us the retirement of the originals.

|

This certainly applies to Laurie Jupiter (Silk Spectre II), who mainly functions as an object of desire for Dan Drieberg (Night Owl II) and Dr Manhattan. Rather than updating this element from 1986 to meet third wave feminist expectations, it has been exaggerated further. Silk’s costume has been modified from a stylishly arousing low cut dress, to a skin-tight PVC suit with a zipper running down the entire front.[19] Not only does this zipper on a PVC suit have sexual overtones of sadomasochism (a fetish), but it also allows easy access to her entire body, suggesting she is ready for sex at any moment – by comic-book standards, indeed a super girl!

Furthermore, there is never any indication of love between her and Dan, only a sexual attraction. Confusing still is her attraction to him in the first place, as he resembles a sex pervert stereotype in his large glasses, flasher’s Mac and floppy hair quiff. The only reason presented in the film is that she turns to him for comfort after her boyfriend, Dr Manhattan, has stopped giving her attention, which implies that she needs a man in her life to define herself, as she is simply an object ‘for masculine desire and fetishistic gazing’ unlike the men, who ‘drive the film’s narrative forward’ (Mulvey, 1975).

Furthermore, there is never any indication of love between her and Dan, only a sexual attraction. Confusing still is her attraction to him in the first place, as he resembles a sex pervert stereotype in his large glasses, flasher’s Mac and floppy hair quiff. The only reason presented in the film is that she turns to him for comfort after her boyfriend, Dr Manhattan, has stopped giving her attention, which implies that she needs a man in her life to define herself, as she is simply an object ‘for masculine desire and fetishistic gazing’ unlike the men, who ‘drive the film’s narrative forward’ (Mulvey, 1975).

|

[19] It should be noted that her attire in the comic did display her cleavage, and consisted of a short skirt, rather than the shorts worn in the film, which is arguably more sexually serving of scopophilia and the male gaze. However her look in the film is more overtly related to sexual fetishism, making her even more of a commodity. This is partly due to a sub-plot concerning Nite Owl II’s fetish, but also seems to reflect a generation exposed to the fetishism of sex via the Internet, and a society that is now more accepting of it. |

Watchmen has not taken a postmodern stance to comment on the institution of female representation in American cinema then. But the film is not without one, minor, redeeming quality regarding female portrayal. The character Silhouette (Apollonia Vanova) is a crime-fighter in the early days of the superhero movement and comes across as the strongest female role in the film due to her assertiveness and lack of need for a man.

|

Unfortunately the only way this seems possible in the world of Watchmen is because she is a lesbian. This implies a fear of strong women in the genre unless they are off the menu, sexually. Even then, she is eventually murdered for her sexuality.

Ironically, her presence does serve as one of the first major signs of postmodernism in the film. Presented in a hyper-reality, as she crosses a street and embraces a nurse during a WWII victory parade, their kiss destabilizes concepts of epistemic certainty and historical progress, becoming one of the first indications that Watchmen is set in an alternative universe. Just not one in which heterosexual women are independent of men. |

|

|

‘HOW’S IT GOING DOWN THERE?’[20]

THE SECRET IDENTITY OF THE WATCHMEN

As previously discussed, the ending of the film blurs distinctions of the genre by allowing the ‘villain’ to accomplish his goals. In addition to this it engages further postmodernism by questioning the notion of a fixed identity. After the attack on New York and Rorschach’s death, Nite Owl II begins to physically beat Veidt. After a while he realises that Veidt is not retaliating, and ceases. As Veidt then refuses his request to fight back, he seems at a loss and walks away, as his sense of superhero identity cannot be defined in relation to the ‘other’, as Veidt is not a typical comic-book villain. Nite Owl II finds himself having to reconsider his actions and postulate that there is an intangible enemy he cannot fight, and is therefore at a loss due to the lack of a universal truth.

The entire film plays with audience expectations of a fixed superhero identity, particularly with the character of Night Owl II. In a costume that is a pastiche of Batman’s (Batman, 1989), Dan Drieberg (his regular name) appears set up as the competent gadget-handy type of superhero. However he lacks the confident, suave, sophisticated and social elegance of Bruce Wayne, who often wears a tuxedo outside of crime-fighting business hours. Instead, as mentioned before, out of costume Drieberg looks more like a sexual pervert. Furthermore, he suffers from sexual dysfunction, possibly the antithesis of superhero significance in male readers’ character identification purposes.

THE SECRET IDENTITY OF THE WATCHMEN

As previously discussed, the ending of the film blurs distinctions of the genre by allowing the ‘villain’ to accomplish his goals. In addition to this it engages further postmodernism by questioning the notion of a fixed identity. After the attack on New York and Rorschach’s death, Nite Owl II begins to physically beat Veidt. After a while he realises that Veidt is not retaliating, and ceases. As Veidt then refuses his request to fight back, he seems at a loss and walks away, as his sense of superhero identity cannot be defined in relation to the ‘other’, as Veidt is not a typical comic-book villain. Nite Owl II finds himself having to reconsider his actions and postulate that there is an intangible enemy he cannot fight, and is therefore at a loss due to the lack of a universal truth.

The entire film plays with audience expectations of a fixed superhero identity, particularly with the character of Night Owl II. In a costume that is a pastiche of Batman’s (Batman, 1989), Dan Drieberg (his regular name) appears set up as the competent gadget-handy type of superhero. However he lacks the confident, suave, sophisticated and social elegance of Bruce Wayne, who often wears a tuxedo outside of crime-fighting business hours. Instead, as mentioned before, out of costume Drieberg looks more like a sexual pervert. Furthermore, he suffers from sexual dysfunction, possibly the antithesis of superhero significance in male readers’ character identification purposes.

|

Throughout the film allusions are made to his impotence in connection to his forced retirement from being a caped crusader. Just after we are first introduced to him he walks past a garage sign that has a cartoon drawing of a mechanic gripping an oversized wrench as though it were a mighty phallic erection, which reads ‘We fix em’ – obsolete models a speciality’. The mechanical aspect of his manhood is carried on throughout the film with his flying machine, nicknamed ‘Archie’, which we can view as a metaphor for his penis. In one scene it is described as gathering dust as it has not been out in years.

In a later scene, just after they fail to copulate, Laurie prematurely ignites Archie’s flame thrower (after stroking a suspiciously phallic logoed button). Toward the end of the film Drieberg flies it to Antarctica, where the major ‘action’ of the film is to take place, and has problems with his engines, managing to ‘pull it up’ only in the nick of time, but omitting it from the climax of the plot as it has to ‘take time to fire up again’. Further references include his choice of take-away Chinese meal (indicating he is limp as a noodle), a comment about his inactivity due to ‘Tricky Dickie’ (a double entendre overtly referring to the Nixon-Keane Act that prevents the practice of masked heroes in the film), a camera shot of him at the top of some stairs that back-tracks down some railings as though they were his flaccid penises, and his use of a laser gun that goes off too quickly and proves useless in a fight sequence. In addition to this, in one scene Rorschach describes him (or rather his penis) as a ‘flabby failure who sits whimpering in his basement. Why are so few of us left active, healthy?’ just before ascending a building, highlighting his own phallic potency by comparison. [20] Laurie Jupiter asks her boyfriend Dan Drieberg about the machine in his basement at the end of the film. The machine in question is much more than just a flying vehicle…

|

This is not just schoolboy innuendo however. The impotence subtext not only contradicts notions of superhero identity, but serves to peek into the cracks of the grand narrative of caped crusaders. Normally compressed into a desire for justice in most genre films, Watchmen delves into the psychology of superheroes to reveal answers to questions we never thought of asking. After failing to copulate with Laurie, Drieberg is seen standing naked in his basement, looking at the crotch of his superhero costume, suggesting that some answers to his problem can be found there. Not only is this issue of impotency and image of a podgy superhero a break from the conventions of the genre, but as Elizabeth Stephens points out in Mysterious Skin, it is a break from the conventions of mainstream American cinema, because generally ‘the universalised male body has effaced itself as an invisible norm (2007, p172).

Later in the film he is able to overcome his penis trouble by returning to his costumed life and successfully practices intercourse with Laurie. The implication here, as they embrace naked afterward with her PVC suit discarded on the floor like a spent condom, is that he has a need of costumes (and the alter ego that comes with them) in order to have sex. This does not mean that he is consciously fighting crime solely to satisfy his sexual desires, but that it is a driving force of his actions, a necessary indulgence of his libido to satisfy his id. It is a matter never really discussed in Spider-man (2001) or Superman Returns (2006), or any other superhero film, possibly for fear of undermining their very foundations.

As though that weren’t enough of a departure from the regular precepts of masculine superheroes for Drieberg, the film also tampers with it further, by hinting that he is flirting with homosexuality. In one instance he bonds with Rorschach, holding his arm a beat longer than is comfortable for two heterosexual males. Another instance is set during an investigation of Veidt’s office. Veidt, who Rorschach suspects is a homosexual,[21] is not present, so he asks ‘What nocturnal proclivities entice a man with everything into the night at this hour?’ Drieberg, gazes out the window as though he were longing for those same ‘nocturnal proclivities’, and along with Veidt, destabilizes the final assumed bedrock we had of male superheroes.

Later in the film he is able to overcome his penis trouble by returning to his costumed life and successfully practices intercourse with Laurie. The implication here, as they embrace naked afterward with her PVC suit discarded on the floor like a spent condom, is that he has a need of costumes (and the alter ego that comes with them) in order to have sex. This does not mean that he is consciously fighting crime solely to satisfy his sexual desires, but that it is a driving force of his actions, a necessary indulgence of his libido to satisfy his id. It is a matter never really discussed in Spider-man (2001) or Superman Returns (2006), or any other superhero film, possibly for fear of undermining their very foundations.

As though that weren’t enough of a departure from the regular precepts of masculine superheroes for Drieberg, the film also tampers with it further, by hinting that he is flirting with homosexuality. In one instance he bonds with Rorschach, holding his arm a beat longer than is comfortable for two heterosexual males. Another instance is set during an investigation of Veidt’s office. Veidt, who Rorschach suspects is a homosexual,[21] is not present, so he asks ‘What nocturnal proclivities entice a man with everything into the night at this hour?’ Drieberg, gazes out the window as though he were longing for those same ‘nocturnal proclivities’, and along with Veidt, destabilizes the final assumed bedrock we had of male superheroes.

|

[21] Clues to back up Rorschach’s suspicions would include a file on Veidt’s computer with the title ‘boys’, the pink-purple triangle motif of his company (an association of gay pride), his brightly coloured suits, his mastering of a large exotic feline ala Siegfried and Roy, and the fact he has a secret identity as the film’s villain despite being ‘out’ to the general public as a former superhero.

[22] Walter Kovacs’ (Rorschach) placard. |

‘THE END IS NIGH’[22] JUDGEMENT DAY FOR THE WATCHMEN

Throughout this article Watchmen has proven itself to be a purveyor of postmodern enlightenment. It has demonstrated a preference for postmodern narrative and blurred the distinctions of genre. It has enlisted the use of repetition in meaning rather than function to demonstrate a simulacrum of human nature throughout time. By questioning notions of superhero identity it has destabilised audience perceptions of a grand narrative. However it has also proven to be a selective purveyor, employing it in some areas and not in others. While it questioned the institution of masculinity on film, it chose to remain silent (and arguably even regressive) on that of female representation. |

ASSESSING THE POST-MODERN APPROACH

That suggests that postmodern critical theory is a successful method of approach, having highlighted a self-awareness in the film while simultaneously pointing out its prejudice, demonstrating that it is not a mono-toned approach. While postmodernism may have an ability to undermine grand narratives, it is probably something most filmmakers avoid with good cause. Once genres have been shown as flawed concepts, it limits the possible storytelling of future texts. Yet at the same time that proves the value of postmodernism, as it has an impact that demands future texts’ progress.

However it seems only of any practical use as a critical approach toward broader concepts such as genre, as when it is used in more detailed matters it has the unfortunate tenacity of undermining all meaning from the very fabric of existence, rendering it impotent as a usable method. Therefore it seems to be of better use as a complimentary approach to broaden other theories, such as historical reception and queer theory, as its application appears universal, which is both a benefit and its drawback.

That suggests that postmodern critical theory is a successful method of approach, having highlighted a self-awareness in the film while simultaneously pointing out its prejudice, demonstrating that it is not a mono-toned approach. While postmodernism may have an ability to undermine grand narratives, it is probably something most filmmakers avoid with good cause. Once genres have been shown as flawed concepts, it limits the possible storytelling of future texts. Yet at the same time that proves the value of postmodernism, as it has an impact that demands future texts’ progress.

However it seems only of any practical use as a critical approach toward broader concepts such as genre, as when it is used in more detailed matters it has the unfortunate tenacity of undermining all meaning from the very fabric of existence, rendering it impotent as a usable method. Therefore it seems to be of better use as a complimentary approach to broaden other theories, such as historical reception and queer theory, as its application appears universal, which is both a benefit and its drawback.

|

|

Before You Go...

If the alternative 1985 setting of Watchmen has got you thinking about the relationship between history and fictional films then our next article may be of use:

From Factual To Fantastic: Issues Of Using Non-Fiction Elements Within Fictional Contexts In Popular Film

Also Worth Checking Out

If the alternative 1985 setting of Watchmen has got you thinking about the relationship between history and fictional films then our next article may be of use:

From Factual To Fantastic: Issues Of Using Non-Fiction Elements Within Fictional Contexts In Popular Film

Also Worth Checking Out

- If the doomsday clock of Watchmen peaked your interest then you might enjoy a further exploration of nuclear war fears in sci-fi movies: The Atomic Age On Film

- For more about the politics of science fiction blockbuster movies check out Avatar: Plot, Politics And Genre

- Sexism and racial prejudice go under the microscope in our article exploring Planet Of The Apes And 1960s America

|

|